Books, blasphemy and the treasury of texts: some perspective

Treasuring, even venerating, the written word is common but we need more perspective and braver public authorities

Treasuring the written word, seeing it as precious, even holy is an idea as ancient as the written word itself. One of the reasons we have any knowledge about those times is because people treated even the most mundane of documents as something to be preserved. Jewish people even have a word for the place they store, more literally hide, the most important texts and books: geniza. In the case of perhaps the most famous geniza, the one discovered in Cairo in 1896, the contents were indeed a treasure beyond calculation:

“The discovery of the documents in the Cairo Genizah has been likened to the 20th century discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. In addition to valuable Biblical and Talmudic documents, it gave a detailed picture of the economic and cultural life of the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean region over many centuries. No other library in the world possessed such an array of religious and private documents from the 10th to 13th centuries, when the Fatimid caliphs (10-12th centuries) and Ayyubid sultans (12th-13th centuries) ruled. The genizah revealed a wealth of information from this period, an era previously not well-known in Jewish history. Its leaves described the vital role the Jews played in the economic and cultural life of the mediaeval Middle East as well as the warm relations between Jews and Arabs, through community minutes, rabbinical court records, leases, title-deeds, endowment contracts, debt acknowledgments, marriage contracts and private letters.”

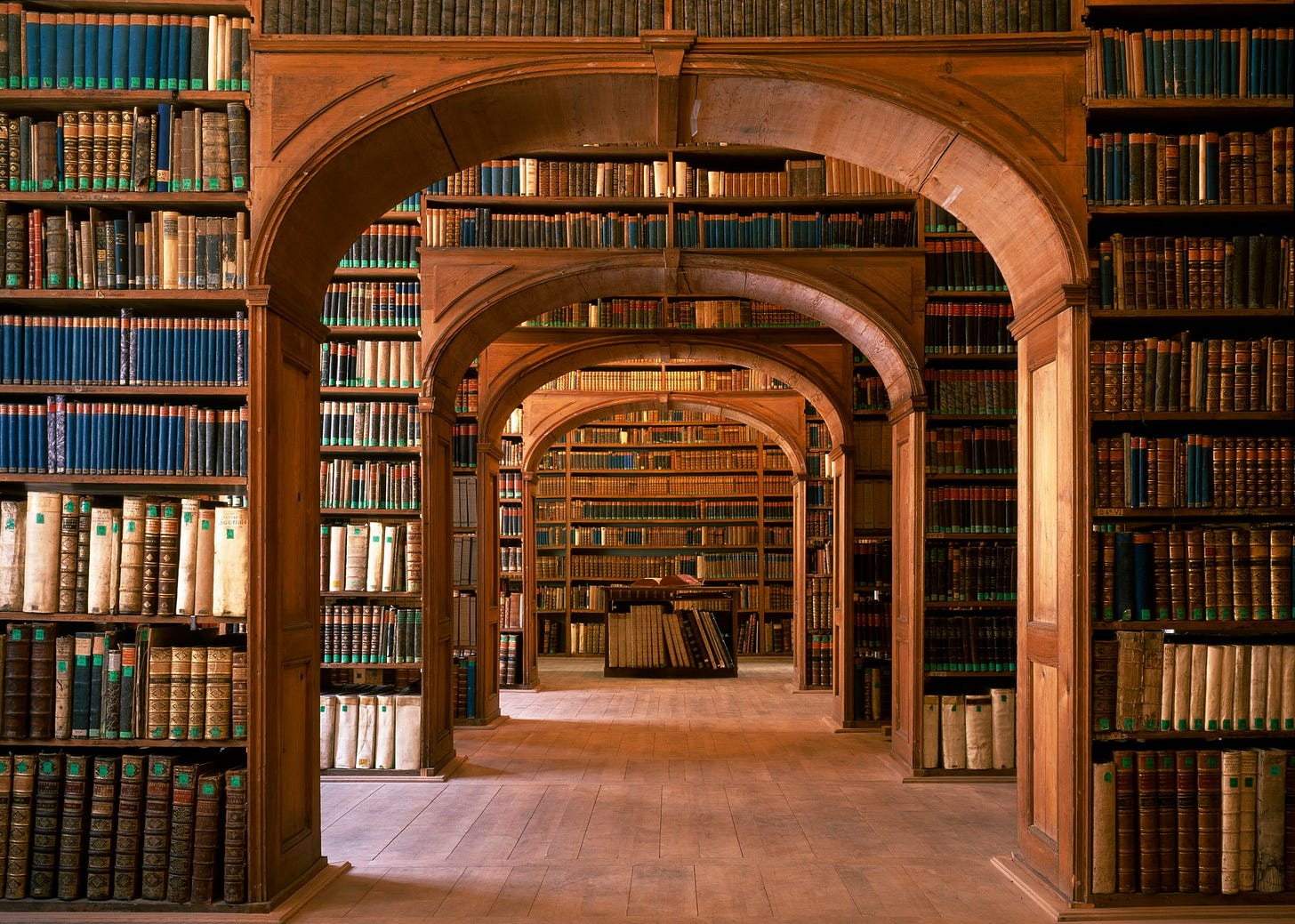

Iris Origo’s book about Francesco di Marco Datini, ‘The Merchant of Prato’ was made possible because the merchant in question kept over 150,000 letters, contracts, ledgers and payment records. Origo is able to reconstruct a sophisticated world of finance, trade and exchange stretching across Europe because Datini insisted on treasuring records of his business and family. Even long after the arrival of printing, people still insisted on storing documents, manuscripts and a host of handwritten records. This collection wasn’t done because we are hoarders but because we retain the idea that written documents, especially those we see as significant or important, should be carefully stored and protected.

In 2021 at a largely Jewish fraternity house of George Washington University vandals broke in and desecrated the house’s Torah scrolls. Jewish and other students, in anger, protested, calling for the university authorities to do more to protect Jewish students on campus. These sacred documents, handed down from generation to generation are important, right at the centre of Judaism. When the gestapo and brownshirts were attacking Jews in Germany, destroying the hidden documents and especially Torah scrolls was commonplace and Jewish people would (and still would today) risk their lives to save these scrolls.

Muslims are no different. The Qu’ran exists today because it was copied again and again with each new copy treasured and protected by the faithful. The book is, to Muslims, the word of God not the ramblings of an 8th century merchant and wannabe warlord. And to destroy a Qu’ran is a terrible thing because you are seeking to silence God. A devout Muslim will approach the Qu’ran with reverence, head covered and hands washed. Reading the book, always in the original Arabic just as those Torah scrolls are in ancient Hebrew, is an act glorifying God and celebrating his word.

Which brings us to Wakefield and a bunch of kids larking about after playing computer games. One of the children, a fourteen-year-old autistic boy, is dared to buy a Qu’ran and bring it to school. When that boy performs this dare there’s some sort of scuffle and the book is slightly damaged. The book in question isn’t, of course, a treasured Qu’ran on a stand in the mosque or even an old book handed down through a family. The book is a modern translation of the Qu’ran into English, the sort of copy that exists by the million across the world and isn’t any more treasured than any other mass produced printed book. We like books, we think them important and feel a little pain at their unnecessary destruction, but we do not think that what happened to an English translation of the Qu’ran in a Wakefield playground represents a grim abuse of Muslims.

I’ve stressed that the book in question is a translation because this matters:

“...it is an Islamic dogma that the Quran cannot be translated. This is to say that Allah revealed it in Arabic, and the Arabic language itself is the body of his words. As scholars have pointed out, in Islam one cannot talk about the incarnation that is the enfleshment of the word but rather of the inliberation that is the embookment of the word. The word did not become flesh in Islam; it became a book and the book was then expanded into uncounted libraries. However, this spirited book was not written, it was recited and a recited book is a book that is embodied within human beings. The sounds and the rhythms of the recitation have a direct influence on the human body”

It isn’t that a book, any book, isn’t important but rather that the Qu’ran in question wasn’t worthy of special reverence in the way local Muslims, urged on by a couple of local councillors, seem to have believed. There’s no suggestion that the boys did anything intended to provoke Muslims yet local Muslims’ disproportionate response to the alleged desecration tells us of a culture, at least among a minority of Muslims, seeking out even the most minor of offences against Islam so as to manufacture claims of blasphemy, of affront to their religion.

Let’s imagine you’re studying ‘A’ level RE and have that same mass-produced translation of the Qu’ran. Do you make notes in the margin, fold down corners on key pages and underline important passages? Does your referring to the book mean the spine gets damaged, maybe a few pages get loose? Is this desecration? According to Wakefield’s Muslim community leaders those actions are a terrible affront to their faith, a gross blasphemy. Or are these Muslim community leaders, especially the ones who see a few votes in their campaign, simply riding a confected anger about an event that wasn’t in any way desecration or blasphemy?

We need to put an end to this sort of confection because we know the consequences. Hundreds of Muslims in Britain, especially those with Pakistani heritage, are devotees of a strange cult around Mumtaz Qadri, the murderer of Salmaan Taseer, then Governor of Punjab. Qadri, we’re told, killed the Governor because he called for the pardoning of a Christian woman accused of blasphemy. Following his execution over 100,000 people gathered for Quadri’s funeral and across Pakistan there were weeks of street protests as imans and politicians urged that the murderer was a heroic martyr for defending Islam.

There is a world of difference between some teenage boys damaging a book while messing around and a deliberate, even provocative, desecration of a holy book. Yet the response of authorities in Wakefield, the school, council and police, hasn’t been to get a sense of perspective but rather to simply take the statements of two local councillors and one imam as a definitive representation of Islamic belief. This, as I know from over 20 years as a councillor (I remember one councillor standing up in a meeting proclaiming devotion of the prophet when the previous Friday I’d seen him and his mates in the Hare & Hounds drinking vodka and coke), is done to make life quieter and easier. In West Yorkshire the police and other public authorities - witness the ‘Lady of Heaven’ protests and the Batley schoolteacher as well as this unfortunate autistic boy - will always call for calm and talk about reducing community tensions. The teacher in Batley and that poor boy in Wakefield are acceptable collateral damage to the police and politicians in their desire not to have a repeat of the 2001 Bradford riots.

The police will see it as a success if nobody is charged with any crime even if a child has to change schools out of fear of reprisal or a teacher has to go into hiding because of persistent death threats from Mumtaz Quadri’s West Yorkshire fanboys. Some are making a distinction here between Islamism and the ideas driving these events in West Yorkshire but it is hard not to see death threats and carefully curated hints about community disturbance as anything other than terrorism. And have no doubt that the evil voices of Islamist terrorism will see the over-reaction in Batley, Bradford and Wakefield plus the supine response from public authorities as an opportunity to exploit, as another grievance to use in their attack on secular culture and Christian tradition.