Bradford: how not to do regeneration (as I found out the hard way)

When I moved to Bradford in 1987, my boss Judith Donovan, said, “150 years ago Bradford was the richest city in the richest county in the richest nation in the world. This was once Beverly Hills"

When I moved to Bradford on the 27th July 1987, my new boss Judith Donovan said to me, “150 years ago Bradford was the richest city in the richest county in the richest nation in the world. This was once Beverly Hills”. I may have slightly misremembered Judith’s precise words but definitely not the sentiment. Bradford was a great city, the capital of the business that made England, the wool trade. I’ve lived here ever since.

Bounded by Bank Street, Hustlergate and Market Street, bang in the historic centre of Bradford, stands Britain’s best branch of Waterstones. This is the Bradford Wool Exchange, a Grade I listed building that, when I arrived in the city, wasn't trading wool but was home to a flea market and some cheap cafes. Like every refurbishment in the city, the Wool Exchange’s transformation into a bookshop was opposed by some and celebrated by others. It would be the catalyst for the city’s return to glory, a trigger for investment in the dozen or so other listed buildings within a stone’s throw of the exchange. Today it is still a bookshop, still hosts the statue of Richard Cobden, West Riding MP and free trade champion. And the city is still struggling.

To understand Bradford’s problem, you may need to start with what it calls itself. Bradford is Britain’s fourth biggest local authority and has been a city for over 100 years. Yet the Council and Councillors routinely refer to Bradford as ‘Bradford District’ or just ‘The District’. There is a faint sort of embarrassment coupled, of course in history-bound West Riding, with the fall out from the 1972 local government reorganisation that lumped Keighley, Bingley and Ilkley in with the old city of Bradford. But if you don’t call yourself a city when you are a city, you shouldn’t be surprised if people that matter agree with you. For all my time here, including 24 years on the City council and six years as political lead on regeneration and economy, the great and good of the city have moaned about being overlooked while describing the place as if it were a shire county market town.

The second problem is that a large part of the population, most of them perhaps, think the city, and especially the city centre, is a dump. Some will have fond youthful memories of the city of the 1960s and 1970s when wool was still king, the shops were full and the streets buzzed with life. My wife found some old paper bags from Brown & Muff and Bryer’s when she tidied out her late mum’s sewing box - posting a picture of these bags on a Braford facebook forum resulted in hundreds of responses remembering the shops and things associated with the shops. To appreciate Bradford’s problem, we need to think about why such things have gone and why, when other places found other high value uses for these spaces, Bradford did not. The Wool Exchange proved to be an exception not a catalyst of a trigger.

Which brings us to, for most people even today, the real villain of the piece, Stanley Wardley. When you see references to Bradford knocking down its heritage - the Swan Arcade, the Mechanic’s Institute, Kirkgate Market - the finger points to Wardley, the City Engineer and Surveyor from 1946 until his death in 1965. It was Wardley’s vision of a city with free-flowing traffic and modernist buildings that, for many modern Bradfordians, scarred the city forever. Prince’s Way, Hall Ings and Westgate became four-lane highways as unnecessary Victorian and Edwardian office buildings were flattened. A ring road that wasn’t a ring road was built allowing traffic to by-pass the city centre but everything seemed slightly disconnected, the motorway stopped two miles from the ring road, the outer road developments appear as if they were defeated by Bradford’s south Pennine topography.

But what killed Bradford city centre wasn’t Wardley, despite his best efforts, and the city thrived (at least as much as any city in England thrived) through to the 1980s. When I arrived in Bradford, Brown & Muff was still a department store and Bryer’s still sold cloth and haberdashery across the road. But these were the last days of the city’s glory, the industrial decline of the 1970s and 1980s, not just the weavers and woolcombers but International Harvesters, Bairds TV and a host of other firms, left Bradford relatively poorer than it had been since the 1850s. The money had run out, literally as for good and bad reasons people took their remaining cash and decamped outside of the city. Some returned now and then to catch a show at the Alhambra or visit a favourite shop or restaurant but most didn’t. And without money a city doesn’t work.

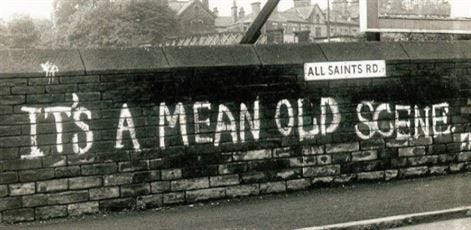

We arrived in the age of regeneration as the city’s leaders sought ways to stop the haemorrhaging of business from the city (half of Leeds’ top law firms were once the top law firms in Bradford) and to attract a new generation of commerce, leisure and pleasure to Darley Street, Kirkgate and Market Street. But while the council, Chamber of Commerce and others sought to boost the city - ‘Bradford’s Bouncing Back’ is the best remembered slogan (made all the more famous by being part designed by David Hockney) - the flight of money continued, some driven by racism but most by people looking for a different, better place to live out their lives. Indeed the slogan that best summed up the city turned out not to be the brainchild of us marketers but some graffiti scrawled on a stone wall in All Saints Road, Little Horton - “It’s a Mean Old Scene” proclaimed the writer in two foot high capital letters captured the feelings of many in a city facing decline but still proud of its history, heritage and cussedness. Jim Greenhalf, veteran journalist on the Bradford Telegraph and Argus, chose the words as the title for his 2002 history of modern Bradford.

In May 2000 I found myself as Portfolio Holder for Regeneration and Economy in a new Conservative-led leadership team. It was an odd time, a sort of regeneration hiatus with most of my time at first being tied up in the problems with Odsal Stadium and the ambitious ‘superdome’ scheme that had fallen apart. But we’d been elected with a pledge to deliver a new master plan for the City Centre, to have another go at stemming the centre’s decline (with an accompanying pledge to develop a similar plan for Keighley, Bingley and Shipley). After a false start doing its own plan, Bradford was picked - how I hate these Heseltine-style beauty parades to get national government funding - for the government’s city regeneration scheme resulting in a new city regeneration company and a master plan prepared in our case by leading urbanist and architect, Will Alsop.

The masterplan was a delight, creative and challenging while showing an appreciation of Bradford’s dilemma. The problem was that Alsop also proposed two things that would come to dominate all the debate about the plan - the demolition of the 1930s Odeon building and the scrapping of proposals for a new shopping mall to replace the 1970s Broadway developments. Once a head of steam was behind stopping these parts of the plan, there was no chance at all of the main principles of Alsop’s ideas getting any consideration. Worse still, Bradford Centre Regeneration was led by old school property and planning people who believed they needed to turn Alsop’s plan into a ‘real’ plan focused on levering property values and using regeneration funding to attract private investment from big developers. It was as if they hadn’t read the masterplan. We jetted off to Cannes, hosted any developer who could find Bradford on a map and threw more curry banquets than you can imagine. Meanwhile, having made the case for the shopping centre, I knocked down Broadway (not me personally but demolition contractors employed by the council) leaving what became infamous as the ‘hole in the ground’.

None of this worked. For sure, we have a shopping centre, the Odeon is being transformed by big public sector loans into a concert venue, city park with its fountains was built, and we have around 3,000 flats and apartments in refurbished and new-build blocks. But the fundamental problem - there isn’t any money - remains unresolved and it is clear that any improvements that do happen are entirely a consequence of Bradford Council using regeneration funding and public borrowing. The Council is moving the markets into a new building on Darley Street (made possible by knocking down the old Marks & Spencers that the company had vacated), proposes to knock down the brutalist lumps of Kirkgate and Oastler markets and is planning more pedestrianisation and open space - making for a very different city from the Victorian one that Wardley transformed in the 1950s and 1960s.

The headlines of Alsop’s master plan (or what should have been the headlines but weren’t) were that Bradford has little or no genuine land value in the city centre and that the way to proceed was to knock down all the rubbish, dig up most of the roads and build a park. Alsop quite specifically proposed no new buildings, merely hinting that if you change the environment you change the values. But we ignored this underlying message preferring the comfort of the established regeneration orthodoxy where public finance is used as seed capital to lever in private finance, all predicated on the idea that new shiny buildings will create land value. This may work in East London, it probably works in Birmingham and Manchester, just about makes sense for Leeds, but would never work for Bradford where land values were already, in effect, negative.

If you’ve been to Bradford City centre, you’ll know that it contains one of the finest collections of Victorian city architecture anywhere in the country. From the amazing cluster of mills and showrooms that is Little Germany to the grand storehouses of Goitside, Bradford has more listed buildings than any comparably sized city, it is a treasure house of Victorian magnificence. And all this glory is both a blessing and a curse. People ought to flock to the world’s best Victorian city in the same way they go to Georgian Bath and mediaeval York. But they don’t because all that glory, bar a few examples like the City Hall, the Wool Exchange and the Midland Hotel, is in half-empty, often semi-derelict, rows featuring cheap shops assuming it isn’t just a boarded up space. A walk via Thornton Road, from City Hall to the top of town takes you along the Goitside, you can even take the risk and walk along the goit itself - nearly half a mile of wonderful architectural dereliction. In Birmingham or Manchester this would be buzzing with life, the old storehouses and mill buildings turned into apartments, bars and restaurants. In Bradford the only life is the rat and the only thing growing is buddleia.

For me, the question for those who are interested in transforming cities like Bradford is how much do you want this to happen? Up to now the expectation of regenerators has been that we arrive with dollops of government cash, spend it on ‘core’ or ‘anchor’ projects and then sit back while the private sector swarms round that investment bringing jobs and money and tourism. It is clear that this strategy doesn’t work unless there is something else that happens. This ‘something else’ could be something like the BBC relocating to Salford or improved transport links but whatever it is that ‘something’ has to involve people with money going and spending that money. Not investors but consumers. Bath is successful because lots of consumers go there to spend their money. Closer to Bradford, Harrogate does well because people go there and spend money. And because of the money that’s spent makes for places where people spend money, people with money go to live there.

Shortly before I retired from Bradford Council, there was another of the repositioning programmes, ‘The Producer City’ we called it. We even had a ‘Producer City Board’ and sub-boards all chatting about how Bradford could ‘produce’ more. The problem is, I would say now and then, that we really want to be a ‘Consumer City’ not a ‘Producer City’. It isn’t that we don’t need jobs, industry and commerce but rather that the places we talk about whenever city regeneration is mentioned are all focused on consumption - leisure and pleasure - rather than the dullness of work, of production. If you draw a map of places from where you can reach Bradford city centre in under an hour by car or train there’s a catchment of five or six million people, plenty of whom have money to spend. They aren’t spending much of it in Bradford.

If using regeneration cash to lever in private funding doesn’t work for Bradford we need a different approach. And it isn’t talking about being a producer city or investing in skills. The idea sits in that 2002 master plan of Will Alsop’s - knock down the rubbish and build a park. Rewild the city centre, pedestrians it all, plant some woodland, maybe an orchard. Take over those rows of derelict offices above empty shops and let them out to homesteaders - they get a free rent for a year or two on the proviso they restore the part of the building we’ve rented them. And do the grand schemes like reopening the Bradford canal and building a bridge across Hamm Strasse to the Central Mosque.

Bradford was once the richest town in the richest county in the richest nation in the world. The legacy of that wealth is there to form the basis for the City’s future wealth. But only if we stop looking back to what once was and stop believing that regeneration is about office blocks, property developers and international retail brands. Like the house restorer who strips the grand old building back to its wonderful basics, we should do the same. We once spent £500,000 asking one of the world’s great architects what we should do to fix up the city. Will Alsop told us. He was right. It is a shame we ignored him.

That was an interesting read. There's many similarities to Swindon, by the sounds of it. The town centre is mostly a disaster, although more modern. I'm not sure if prosperity is different. Swindon is prosperous, but the town centre is a dump, while most of the higher end retail is business parks or people going to other towns like Bath or Reading.

A few points for you:-

- Bath is very much about the proximity to London, especially in terms of foreign tourists. Foreign tourists essentially visit London. From there they will do some days out, which means a coach trip in a day, which means places within a couple of hours: Windsor, Bath, Stratford-Upon-Avon, Stonehenge.

- The internet, supermarkets and cars have really destroyed many shopping areas and created wastelands. I mention Swindon. I could also mention Northampton and many towns around Manchester. People used to go to town to buy a CD, to buy some socks and maybe a new coat. The internet has replaced the first, Sainsburys does the second, which really leaves the 3rd, and as women now have cars and don't need a new coat that often, they will choose to travel to a nearby city with the best range. Which has led to some places really losing a lot of their town centres and other places growing. Bath has more retail space than ever. Reading is the same. It then becomes like gravity, that you can go to Bath and do 3 or 4 bits of your more special shopping in one go, easily.

On that last point, much has been done by government to try and "bring back the high street" but it is like holding back the tide. People like this setup better than just going to their little town centre. So, do something else with it. I have to say that Swindon council get this. They're converting a shopping centre into apartments, recognising that lots of people want to live near the station. I think much of our planning law about change of use is also a hinderance to many towns. Houses that were converted into shops over a century ago should be turned back into houses.

I totally agree with your comments, yet, let us create a CAZ zone, say the Council, to limit commercial traffic which cynically extends like an amoeba towards Shipley/Bingley to capture a main arterial road traffic. Also let us grab a load of money from parking charges say the Council. Oh! Dear! is the response, visitors have gone down. I know let's put up parking charges. As for the social, community disconnect and problems, we know why that is occurring but it cannot be said. My squirrels think the Government auditors have been to Bradford, I wonder why?