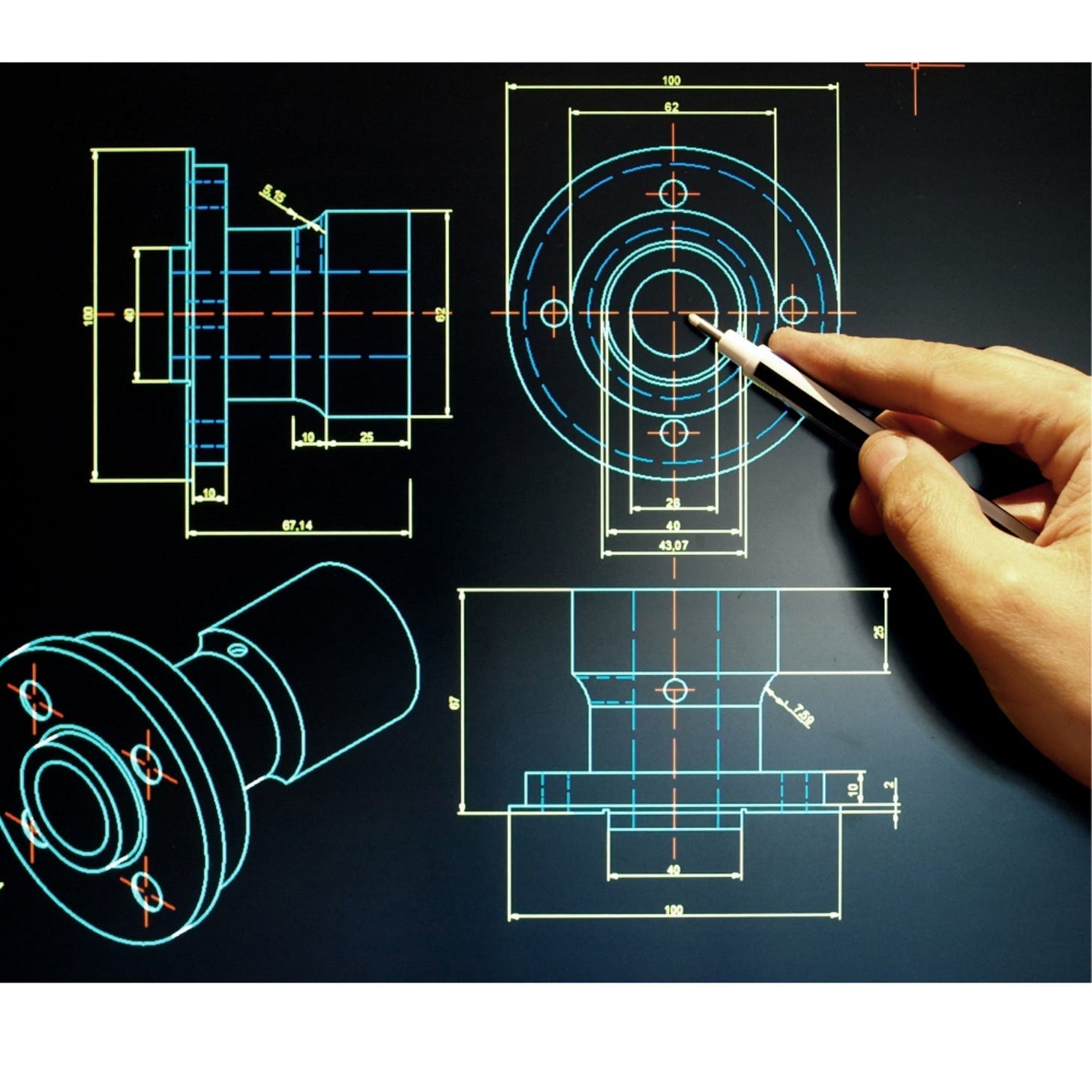

Government by targets doesn't work but neither does government by engineering drawing. Free markets work.

Successful economies grow because they allow enterprise the space to succeed (or fail) not because of any industrial strategy, regeneration programme or intervening before 'breakfast, lunch and dinner

Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch has announced that a future Tory government would repeal the 2008 Climate Change Act:

“We want to leave a cleaner environment for our children, but not by bankrupting the country. Climate change is real. But Labour’s laws tied us in red tape, loaded us with costs, and did nothing to cut global emissions.

Previous Conservative governments tried to make Labour’s climate laws work – they don’t. Under my leadership, we will scrap those failed targets. Our priority now is growth, cheaper energy, and protecting the natural landscapes we all love.”

The significance of this shifted position isn’t simply about climate change policy but about the use of legislation to create binding, immutable targets. What happens with climate policy is reflected also in a host of other areas of government, from planning and housing through to defence and international aid; parliament agrees to binding rules overseen by an ‘independent’ body or to a given target for inputs (typically spending) and, in doing so, fixes the strategic course for that area of policy regardless of whether or not that strategy is working.

While there are debates about the reasons for us having some of the world’s most expensive energy, the absolute reality is that this expensive energy does, as Badenoch recognises, result in the deindustrialisation of Britain and, beyond manufacturing, in higher costs across business and commerce. And Britain’s higher energy costs are primarily (if not entirely) down to deliberate policy decisions that track back to the 2008 Climate Change Act and to the 2019 extension of that act to make its targets legally binding. The problem is that the strategy of, in effect, using high energy costs to force behavioural change on business and consumers (while promising jam tomorrow in the form of lower bills) is leading to people who fundamentally support the process of emissions reductions turning away from the Net Zero target. As Octopus Energy has observed:

“The UK’s net zero ambitions remain popular, but public support is at risk. While more than twice as many people support net zero than don’t (43% vs. 20%), seven out of ten supporters (71%) said their backing hinges on energy prices not rising. Lower bills would boost public support for net zero even among sceptics. A staggering 65% of people who currently oppose net zero would reconsider their position if the policy led to lower bills.”

Because bills are currently rising, the overall policy (whatever the likes of Gavin Barwell, architect of the May government’s binding targets, say) becomes increasing poisonous as more and more people stop buying the fiction that Britain’s high energy costs are down to wholesale gas prices not the structure of subsidy and support for the renewable energy market. If you want to meet Net Zero by 2050 then you need to adopt a different strategy, one that doesn’t use targets imposed, essentially arbitrarily, by a QUANGO, the Climate Change Committee and monitored through an inflexible ‘carbon budget’. Setting an objective (‘reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050’) doesn’t require that there is just one strategy and, given that the current strategy, turbocharged by the increasingly bonkers rhetoric of Ed Miliband, isn’t working, what Badenoch is setting out represents the first challenge to the consensus around climate change policy not based either on denying climate change itself or else on simplistic NIMBY responses to new energy infrastructure.

There is a sort of Stalinist overlay, all tractor statistics and production quotas, to this sort of policy-making. Political leaders stand at podiums announcing new improved targets for housing, recruitment to the military, how much of GDP is given away in overseas aid, and how much we’ll reduce emissions this year and pass across the responsibility for those targets to ‘independent’ or ‘arms-length’ bodies often granted extensive powers over pricing, investment and production. The reason why we don’t have enough houses, have to recruit soldiers from Pacific islands or Himalayan valleys, and have obscenely expensive electricity is because the bodies that oversee these functions believe that they have to manage the entirety of each market with the inevitable shortages, gluts or high prices that this approach creates.

I hope that Badenoch and the Tory Party’s belated recognition that the current Net Zero strategy has failed reflects a conversion back to the Thatcherite idea that the way to deliver change is to create the right market incentives not to control or direct the market. A good place to test this idea would be another area of abject state failure in Britain, the housing market. If we accept that we need a load more houses - some say four or even five million - then the way to achieve this isn’t to micromanage targets for district councils but to scrap the system that makes those targets necessary. I fear, however, that the legacy of Theresa May’s administration won’t go away since the ‘exciting’ future of the ‘centre-right’ seems to involve more, not less, state direction of the economy:

“Pass a Made in Britain Act to frame a focused push on semiconductors (including compound chips), life sciences, defence manufacturing, chemicals and clean manufacturing. Introduce a UK capability test in public procurement, consistent with GPA rules, that prioritises domestic capacity, security, resilience and skills transfer rather than nationality. Sign regional growth compacts around real clusters, using the Innovation Clusters Map published yesterday as the baseline. Universities and further education providers will build skills pipelines.”

This sort of ‘regeneration’ approach (something that old big government centrist Michael Heseltine would enthuse about) has never worked. It sounds good with all the talk about ‘clusters’ and universities, skill pipelines and innovation but we’ve been there before - in the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s and 2000s - without any noticeable impact on the success of places in England outside London and its exurbia. The work, from James Yucel at UK Onward, doesn’t represent a fundamental shift to strategy but rather a change to bureaucratic process. We change from one process (law, regulation, targets) to a different process (engineering drawings, build schedules) without appreciating that economic growth doesn’t come from FDR-style New Deal programmes but from entrepreneurs and their businesses meeting the demands of consumers through creativity, innovation and hard work. Yucel and his colleagues are right that excess regulation, whether related to planning, nature, labour policy, or the environment, is the single biggest barrier to growth in Britain, they are wrong to believe that the state can create growth itself.

I hope that the statements by Kemi Badenoch about Net Zero represent the first steps away from the state-managerialist consensus that dominates politics across Europe and back towards the fundamental truth we learned back in the 1980s. Successful economies, even those with big welfare states, grow because they allow enterprise the space to succeed (or fail) not because of any industrial strategy, regeneration programme or a programme of intervening “before breakfast, lunch and dinner” as Lord Heseltine put it back in the day. Persuading the likes of James Yucel and Onward UK to embrace the idea of free market capitalism should be the very first task since, if we don’t, the result will be just another failed industrial policy wrapped in a flag.

Goodhart’s law: When a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure.

Once a goal is set, people will optimize for that goal in a way that neglects equally important parts of a system....such as maintaining economic viability.

So, why did she change her mind? Does she explain that? She repeatedly voted to back Net Zero for what, 5, 6 years? What about my former MP? Is he still the candidate, someone who enthusiastically voted for it all. I can only assume he'll stick by that when back in office, rebelling against Kemi.

The problem is, I don't know, and if I'm wrong, I'm stuck with him for 5 years.

The sort of people who lead Reform are the sort of people who were against Net Zero when it was still rather fashionable, while everyone thought that renewables would totally work, rather than it being more complicated than that. They were the people who objected to mass migration in the face of being called racists. They were heirs to Blair when it was popular, and just before that train derailed. The Conservatives generally strike me as people who move with the wind. Who aren't really that bothered about doing much but what is popular for the next 5 minutes. I see little in the way of philosophy to them that allows me to understand what they will actually do.