How Dungeons & Dragons changed the world - and our lives

D&D is the single most important game created in the 20th century - it changed the world and its spirit changed my world

A few years ago Ben Riggs wrote down the best summation of how Dungeons and Dragons was created. Some might quibble about what happened after this first part but it remains true that Dungeons & Dragons was created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson back in 1972. As Riggs put it:

“Once upon a time, Dungeons & Dragons was published by a company named TSR, in a magical realm named Wisconsin, where the hills roll like green waves to the horizon, where the cheese is the bright orange of the sunrise, and the winters are long and dark as death. Dungeons & Dragons was created by a brace of midwestern mages named Gary and Dave, and the tale of the game’s journey from a Lake Geneva basement in 1972 to the cultural institution it is today is one of the great stories of gaming.”

You can read Ben Riggs' history which takes you up to the current Hasbro and Wizards of the Coast incarnations of the game. I’m interested, however, in the significance of that original game - the one I first played back in 1978. It is the most important development in games design since the creation of multi-player board games in the late 19th century. And, using Ben Riggs’ words, this is why:

“The premise was simple: players would portray only a single character (an idea he lifted from a game called Braunstein) and would explore underground dungeons where they would face perils and puzzles. Both the characters and the story would persist from session to session, with characters working cooperatively and improving over time.”

Up to this point, other than children’s imaginative playground play, games had always involved a contest between the players and an end. Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) introduced a game where the players cooperate in a contest with the game itself rather than with each other. Coupled with this innovation, D&D also systemised the thing - role play - that those childrens games of cops & robbers or doctors and nurses had been about. Yes role play was still free form but the way in which players’ interest was governed by the characteristics generated by the roll of dice. If your charisma (determined on a roll of three six-sided dice) is high, your character is more likely to be charming and persuasive. The same went for the other main characteristics (strength, wisdom, intelligence etc.) and dice rolling was used to manage the role play as well as the slaying of the game’s monsters.

All of this took place within a fantasy context meaning that a whole bunch of geeky and nerdy teenagers, mostly boys, suddenly started doing something they’d not have done without D&D - acting out a role. Outsiders looking in didn’t, of course, see this, they saw geeky boys playing with wizards, goblins and trolls. This got the same sort of response from many that the fantasy literature the game drew from - I wrote this about the glorious moment when the British pubic voted for “The Lord of the Rings” as the greatest English novel (in a TV show the BBC ran called “The Big Read”):

“...one of my favourite TV moments will always be the expression of utter disappointment on Clive Anderson’s face when he had to announce that “The Lord Of The Rings” was the greatest English novel (or so the public had voted). And I smile serenely at some of the frothing antagonism (and allegations that the book’s vote was somehow fixed by hordes of “well-organised” Tolkien fans) that followed”

Yet those bright nerdy boys were on to something, they were playing the first game system that was collaborative by design, where survival and advancement - there was no end as such - was achieved by working with the other players not by defeating them. Others focused on the seeming naffness of slaying great mythical beasts with magical swords and completely missed the innovation that D&D had brought to gaming - an innovation that spawned dozens (maybe hundreds) of other games in a host of settings from the far future to 1930s Chicago and drawing on crime fiction, horror stories, space opera and dystopian science futures.

The common feature of all these games was that they weren’t PvP, weren’t “player-versus-player”, but were rather players-versus-game. And all used variations of dice-rolling to determine everything from whether your player can seduce the bartender through whether your gun jams to did you spot what ran into those woods. And you won by combining your skills - as determined by the character those dice rolls created - with the skills of other players’ characters. Moreover ‘winning’ was more about having fun than actual winning - D&D players will all have played for a fun hour or two doing little more than shopping, having dinner and visiting the baths.

Pop into your local board game shop today and, amongst the traditional competitive games (as well as role-playing games - RPGs - like D&D) you see a new genre of game designed to be collaborative. This may involve players competing against the game ‘clock’ to escape (in the manner of now popular escape rooms) or else simply collaborating to solve a puzzle. Games have moved on from just competition to a variety of other formats and all of this only came about because Gary and Dave wanted a game system for fantasy combat that enabled questing not merely battle.

Of course role-playing is more problematic than moving pieces round a board in competition with other people moving pieces round a board. And that meant D&D, as the daddy of the RPGs, attracted criticism and opprobrium. While modern accusations of racism and sexism exist (and the game’s owners are perhaps bending a bit too far over backwards in response) the big attack on D&D was a moral panic driven by the presence of devils and demons in the game.

As the post-2010 D&D revival took hold, Gizmodo published an article called “How We Won the War on Dungeons & Dragons” which recounted some of the nonsensical reactions to the game from assorted religious authorities in the USA. The article cites of source that sets out the scale of the moral panic about the game:

“Here, a list of suicides are presented, with location, race, sex, and date of death for each. These are the names that were usually the first ones trotted out when the 'dangers' of D&D were discussed. Along with them, we get some supplemental data - all were white males between the ages of 12 and 18, three were honor or gifted students, all deaths but one involved a weapon, and - the most curious coincidence of all - half of these deaths occurred on a full moon.

The significance that the lunar phase has on these deaths is briefly elaborated upon in this booklet, when the topic of lycanthropy comes up. That's right - BADD is suggesting here that a portion of these deaths (possibly as many as half of them) happen because D&D players are led to believe that they are werewolves.”

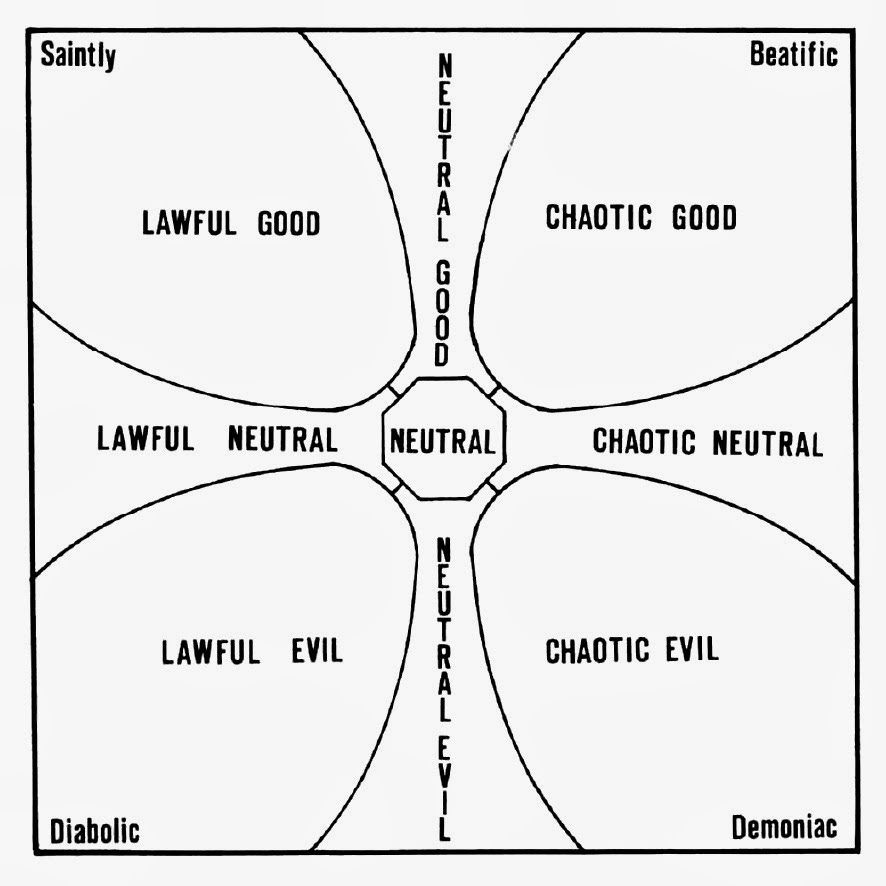

Teen suicides are always a tragedy but the use of a game played by a few of these suicides as a sort of coping mechanism allowing people to ignore the real mental health issues you people sometimes face is sadly too typical of moral panics, whether or not their source is religious authority. The real problem religious authorities - and plenty of other public moralists - had with D&D was that it required players to think about ethics and morals so as to play the game. Gygax and Arneson even came up with an “alignment chart” to help:

As I wrote at the time of that Gizmodo article:

“If you want to live a good life, it has to be on the basis of understanding what that means. You can get out the book and read the (often contradictory) guidance from the ancients or else you can work it out from first principles. And the D&D alignment chart seems to me a good place to start - it tells me that executing the adulteress for her sin may be lawful but it is probably evil at the same time and that saving that adulteress - however sinful she may be - is a chaotic act but also an act of goodness.

Religion told me none of these things. I learnt that god is good and the devil is bad. And that if I follow the rules I will live forever. I learnt nothing about what all this meant, about whether there's a devil or whether that god is all he's cracked up to be.”

This, the idea that society has a moral basis but that we should debate what that means, is the other big thing that D&D provided. Although games are played with different degrees of seriousness, that alignment chart still prompts debate and people still don’t agree what “lawful good” means. Whose laws are they, what are the bounds of good, and so forth. This discussion takes place without recourse to impenetrable tomes of moral philosophy or learned but hard to read religious tracts. Above all, even in a world that acknowledges the presence of gods (and most D&D words do), the moral behaviour of your character is moderated by the interaction with fellow players, by the role-play.

I am pleased that the game remains a success and hope that, in the spirit of the fantasy worlds that spawned D&D, its stewards - players and the game’s owners - recognise that the game changed the world for two reasons. Firstly it made players work together and interact with each other, it gave us collaboration and role-play. And secondly it encouraged players to be creative in their thinking, the game was limited only by the imagination of the players not merely by the framework of the game’s creators. I worry a little - not much - that the cultural pressure of West Coast USA will exert a different, but just as controlling, sort of pressure on the game and its players to that we saw from America’s religious moralists in the 1980s. This would be a shame.

Still, I shall this weekend be on retreat playing the game for untold hours. And talking about it between times. Dungeons and Dragons changed my world, I believe it changed yours by giving a bunch of geeks and nerds a game with role-play, complex moral dilemmas, and demons to slay. What could be better!