If Britain wants better public infrastructure it needs to restore the power of local government to build it

The untidy mish-mash of local provision had built public utilities, enabled housing, laid out roads and, on top of that, provided parks, swimming pools, libraries, schools and public transport.

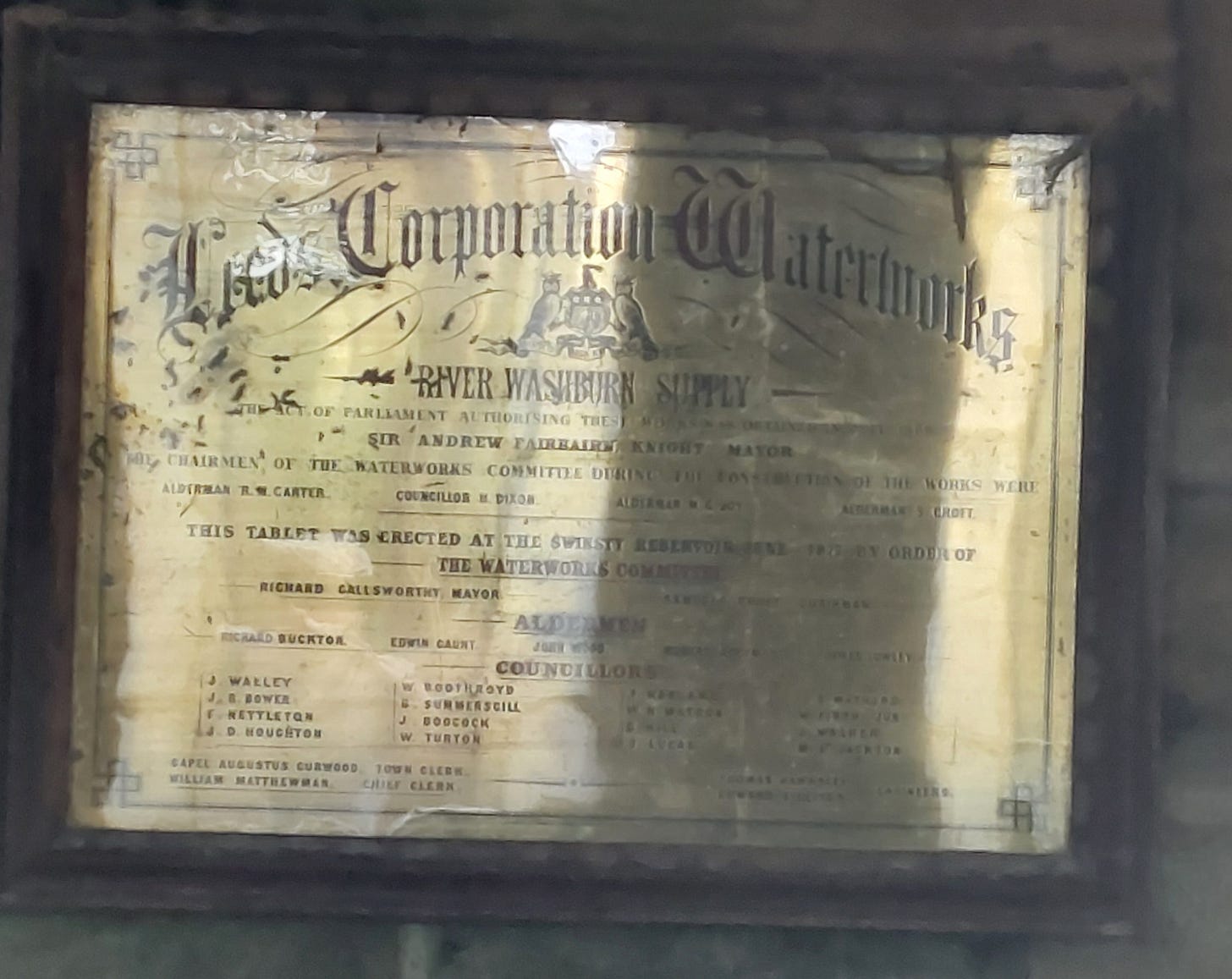

In 1871 the Leeds Waterworks Company, owned by the City Council, began the construction of Swinsty Reservoir, the first of the three Washburn Valley reservoirs that still provide water for the people of Leeds. Like all of these great Victorian projects the reservoirs were built at, as people put it today, ‘scale and pace’. You can visit the reservoir today and, like so much of Britain’s water infrastructure, the place provides amenity for visitors and a home for diverse and interesting wildlife. On the opposite side of the reservoir from Swinsty Hall is an old pumping house, no longer in use but still a fine Victorian building because nothing about the construction of municipal infrastructure in those days was done without grandeur and a sense of permanence. You can peer into the pump house through its original but dirty windows and there, on the back wall, is a brass inscribed plate celebrating the works and listing the alderman and councillors who made up the committee that undertook the development. The plate also makes reference to the acts of parliament that gave Leeds City Corporation the authority to undertake these sorts of works.

The 1869 Leeds Improvement Act (resulting from a process that began with the first Leeds Improvement Act in 1755) gave the council powers to “...improve the streets and becks, and to make other improvements in the said borough, and for other purposes.” It was the last part that allowed Leeds to buy land for water infrastructure 20 miles north of the city. Similar acts were passed granting powers to other cities and towns including Bradford, Wakefield, Huddersfield and Halifax (even up to the 1960s when the Huddersfield Corporation Act 1965 allowed the building of Scammonden Reservoir by Huddersfield Corporation Waterworks). Across England the ambition of local corporations (and local leaders) to improve conditions for people sits in marked contrast to the popular mythology of rapacious, greedy mill-owners caring nothing for the circumstances of workers. And all this was done in a spirit of municipal competition, the rivalries between Leeds and Bradford, Manchester and Liverpool, Nottingham and Derby were provided a kind of arms race of municipal glorification. All made possible by the explosion in municipal wealth created by the success of English manufacturing.

Britain has, it seems, forgotten how to build infrastructure. It is over 30 years since the last new reservoir was opened and 50 years since the last permission to build one was granted. Yet, in the period since the Carsington Reservoir was opened, not only has the population increased but each household also uses a lot more water. It is quite remarkable that we’ve had so few serious interruptions to or limitation on supply. And it isn’t just water but roads, railways, airports, electricity generation and waste disposal. Back in the 1980s the view was that (after various governments had removed the power to improve this infrastructure granted to councils by improvement acts) the solution lay in private ownership and financing. This was the age of privatisation, a time when councils were told not to borrow, and a time when people would seriously (I was one of them) argue that all councils needed to do was meet once a year to agree the contracts. Yet walking round Swinsty Reservoir it is clear that city corporations can - and did - build and manage infrastructure intended for the betterment of ordinary people’s lives.

The problem wasn’t councils. It wasn’t even the capability and capacity to raise finance for development. The problem lay in the creation of public corporations without any effective accountability, the problem lay in the preference for ‘independent’ regulators over ambitious city leaderships, and the problem lay in the way anti-developmentalism, the NIMBY, became a powerful political force built on the bones of planning laws and regulations. The untidy mish-mash of private and municipal provision was ended by the man in Whitehall who, adopting Labour’s nationalisation as a beginning, persuaded Tory ministers that a better way was with national and regional bodies (led obviously by the friends of those ministers and guided by the friends of senior civil servants). Yet that untidy mish-mash of local provision had built the public utilities, enabled the housing, laid out the roads and, on top of that, provided parks, swimming pools, libraries, schools and public transport. In what is probably the single biggest act of collective lunacy, successive governments in Westminster have, since the 1960s, chosen to put an end to local initiative, leadership and ambition. Instead we’re given powerless mayors whose only role is to administer central government sponsored investment and ‘unitary authorities’ that exist to provide a series of entitlements and duties laid down by regulators in London.

The eager crowd of urbanists and city boosters scuttle around telling us how much better (depending on their personal preferences and political biases) places are in Europe, the Far East or America. And how this is because cities have trams, bigger football stadiums or less potholed streets. But none of these experts ever asks why this is the case, why small cities in France have (expensive and underused) tram systems, why a high school in Georgia can build a 10,000 seater stadium, and why that little old hill top place in Le Marche washes its streets overnight. The answer is, of course, local government and local control. If England had not decided to remove powers over development from councils and replace them with national regulations and unsustainable social entitlements then we too would have trams. Even better, we'd have cleaner streets, better parks and that old sense of municipal competition that helped make the centres of Bradford, Huddersfield and Halifax such glories.

A few years ago Bradford Council was debating whether to join a scheme called ‘White Rose Energy’. We were told that this would benefit local people by offering more affordable energy by leveraging (I’m sure that word was used) the buying power of Yorkshire’s councils. Like Robin Hood Energy the business model of entering a very competitive market with tight margins and loads of suppliers was always going to fail. During briefings with officers I made the observation, only slightly in jest, that our Victorian forebears wouldn’t be buying energy on open markets, they'd be building a nuclear power station. And to do this they would have sponsored an act of parliament giving Bradford, Leeds and Wakefield the power to develop, found a suitable spot (somewhere nearby like Goole) and built the new infrastructure. We should perhaps be asking why this can’t happen and how we can get back to the times when people, ambitious for their city, simply got on and built the things we need.

An observation (which in no way means I disagree with you): legislation like the Leeds Improvement Act 1869 were local acts, and therefore subject to private bill procedure in Parliament, which is different from and somewhat more complex than public bill procedure, not least because of the provision for affected parties to petition against the bill and Parliament is acting in a judicial capacity as well as exercising its legislative function.

To circumvent this, Parliament introduced first provisional order confirmation bills (not used since 1980) and then special procedure orders (see Statutory Orders (Special Procedure) Acts 1945 and 1965), which are more streamlined but can still be petitioned against. A range of transport schemes "of national importance" can now be dealt with by order under the Transport and Works Act 1992 and the Planning Act 2008, though this can still result in a public hearing or a local inquiry.

Then, of course, one has the dazzling wonder which is the hybrid bill, a public bill "considered to affect specific private or local interests, in a manner different from the private or local interests of other persons or bodies of the same category".

My only point is, it can complicated.

A good article. Whilst something has clearly gone wrong with local government, it lacks ambition and competence to name but two. The biggest issue is cash, the Victorians had oodles of it because we (they) had the greatest economy in the world at that time and because we had great industries and craftsmen, almost of that is now lost. There are mystical black holes of exorbitant sums around every corner and our growth industry seems to be Deliveroo and Just Eat, powered by a low skilled migrant workforce, which seems only to benefit the Chinese scooter industry. Consequently the regions are subject to the scraps from the table of Westminster if Rayner can wring out Reeves hard enough. God help us!

Unless the new move towards Mayors comes with genuine autonomy and empowerment, for instance to set their own business rates and retain all the revenue, then we'll never again see the heady days enjoyed by the Councillors and Aldermen of the Victorian municipals.