Our planning and benefits systems should support families and children not merely workers

Our planning and childcare systems fail us because they take a narrow economic view, valuing work above family life

I’d like to connect two discussions in national policy - childcare and housing. The recent budget, in the modern manner, sought to address the former issue through paying a lot more money to childcare providers so parents can return to work more quickly. Unsurprisingly the budget did nothing about our continuing and longstanding housing problems that are a consequence of 60 years failing to meet housing needs.

On the housing issue I was struck by a speech in the House of Lords in 1962 by Labour peer, Baron Silkin that set out the scale of the need for new homes at that time:

“...I gave the House the conclusions I had arrived at under a number of various headings, such as the increase that we might expect in population, the numbers required to clear the slums, overcrowding, the need for mobility, the effect of the rising standard of living, provision for old people and so on; and the conclusion which I then came to was that we required 6 million houses to be built over the next 20 years. That was in 1955. Since then we have had built about 2 million houses, and only a week or so ago the Minister of Housing and Local Government made a public statement to the effect that we now required 6 million houses: indeed, he went a little further, because he really said that it was at least 6 million and probably more.”

Even with the slum clearance and council house building programmes of the decade following Lord Silkin’s speech, it is clear that the minimum net new homes of 300,000 per annum was not met even at the peak of this development boom (and Silkin said later in the speech, citing the Alliance Building Society, that we needed at least 8 million - 400,000 per year). And that we have, to put it simply, been playing catch up ever since. The reason for this shortfall is, when you strip away debates over tenure or housing form, that the planning system does not allocate enough land for housing especially in those places where the need is greatest. Our housing problems have been hard baked into the system pretty much since its inception in 1947.

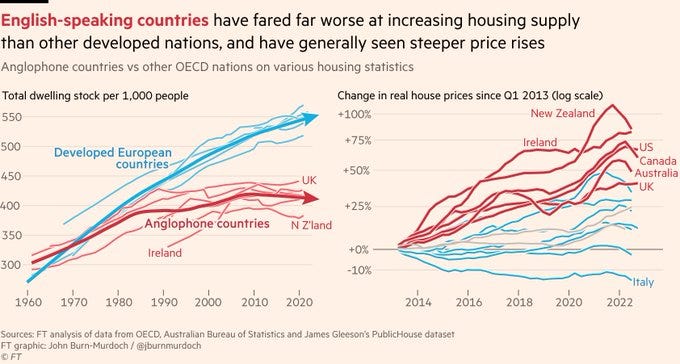

This brings me to some brilliant data analysis presented by John Murdoch in the Financial Times. The critical graph Murdoch presents is here:

It is clear that ‘anglophone’ countries diverged from European countries in meeting housing needs some time in the 1970s and 1980s. For the UK the diversion became most stark in the second half of the 1990s (proably a consequence of PPG3, a ‘brownfield first’ policy) but overall it is plain that the numbers of units per 1000 people in the English speaking world has fallen significantly behind Europe. Murdoch seeks to explore why this is the case and latches onto a single housing type - the apartment - as the reason. Up to four in ten Europeans live in apartments compared to less than a fifth in the anglophone countries. Therefore, Murdoch suggests, we should look to urban density as the problem with people’s preferences for ‘single family homes’ or similar the reason for the lack of delivery on building new homes in the UK and other English speaking countries.

Given what Lord Silkin tells us about government and sector estimates for housing need in the early 1960s, it is hard to see how the shortfall in housing delivery can be blamed on Britons, Aussies, Kiwis and Yanks preferring a different housing form to Europeans. We didn’t stop living in apartments in the 1980s, by which time European housing (large parts of which is post-WWII) was already dominated by flatted living.

In 1974 Professor Peter Hall published two volumes entitled ‘The Containment of Urban England’ where he and his team reviewed the effects of England’s planning system on development and the economic wellbeing of the population. The conclusion was that the planning system was a drag on income distribution and its outcomes were perverse:

“None of this was in the minds of the founding fathers of the planning system. They cared very much for the preservation and the conservation of rural England, to be sure. But that was only part of a total package of policies, to be enforced in the interests of all by beneficent central planning. It certainly wasn’t the intentions of the founders that people should live cramped lives in homes destined for premature slumdom, far from urban services or jobs: or that city dwellers should live in blank cliffs of flats, far from the ground without access to play-space for their children. Somewhere along the way, a great ideal was lost, a system distorted and the great mass of people betrayed.”

The planning system didn’t just act, through the curse of Patrick Abercrombie, to contain urban England but it made a system of single uses separating homes from work and people from social amenities. Above all the system, by privileging the fortunate few who owned property at the urban fringe, acted to constrain the central social task for humans - raising families. The planning system, not as it was intended but as it operated, became in effect anti-child. And alongside the great opportunity brought for women by the liberation of the 1960s and 1970s, society’s relationship with children and family life changed.

Today, as the budget showed, there is a sense that children are a luxury good rather than central to human society. Moreover, while the Chancellor was proposing huge sums of subsidy for childcare, this was done with the explicit aim of getting parents - women, if we are honest about it - back into work. As Conservative MP, Miriam Cates observed, there is financial support for mums who want to go back to work but nothing for mums who would prefer to stay home and raise their children. The £6,000 that the chancellor offers to mums is entirely linked to them working - no job, no money. Our hyperliberal preference is for the short term economic benefit of more people in the workforce rather than the longer term social benefit of strong families with children. The only reason cited for subsidising looking after children is economic with all other benefits from a society with more children ignored or dismissed.

For a lot of women returning to the workforce it isn’t a welcome return to a career after the shortest of breaks possible but rather the financial imperative of modern life. Women return to work earlier (and have fewer children) because that is, as they see things, the only way to afford a family. Moreover the jobs they return to aren’t high flying roles but ordinary, everyday and mundane jobs (and none the worse for that, not everyone wants to be or can be the boss). The biggest reason for this financial imperative making women’s, now subsidised, choice for them is housing costs. Most of my generation were brought up in homes afforded with the wages of one person, today only the very wealthiest stand a chance of affording their home with just one full time wage. And our fathers were not doing top jobs either but straightforward jobs as tradesmen, as clerks and as junior managers. We should, in planning the future, begin to ask how it is that we return to a world where the government doesn’t use a combination of subsidy and a sort of ‘work is noble’ kind of moralising to ensure that women who’d rather do the full time and important job of raising kids go back into the ‘productive’ economy. The whole scheme seems little different from paying to take in each other’s washing.

The same goes for the argument that it is time for Brits to get used to apartment living. The reality about very dense cities like Milan or Barcelona is that they have very low levels of fertility - there aren’t any children because there isn’t the places or the safety to raise them. Yet the dominant opinion among pro-housing campaigners is that we need more dense urban areas, more of those ‘blank cliffs of flats far from the ground’ that Peter Hall described. And that a diverse, mixed use suburbia is not something we should encourage because suburbs are naff and people there have cars.

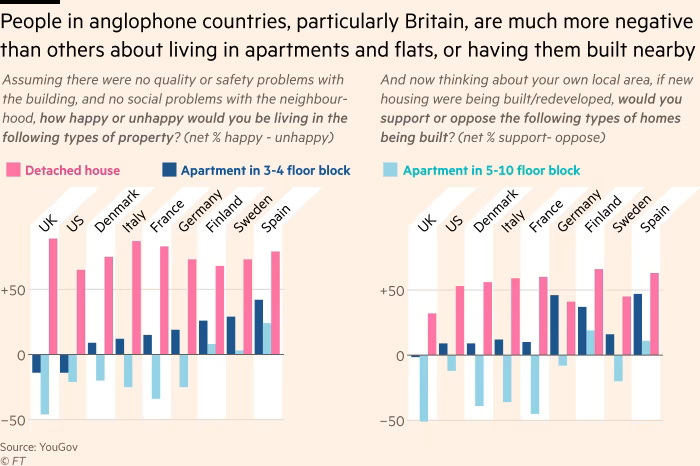

But even in the FT’s analysis it is clear that the most popular housing form (or the forms they tested) is the detached house.

So people on the continent are slightly more happy with apartment living but the separate family home remains everywhere the kind of home that people like most. Far more important to our understanding of the problem is that English speaking countries have planning systems that favour individual representations on applications:

“...the planning regimes in all six anglophone countries are united in facilitating objections to individual applications, rather than proactive public engagement at the policy-setting stage.”

The FT, however, like so many pro-housing campaigners, then gets trapped into the treatment of ‘low density’ as a problem when there’s no evidence supporting this contention. We do need systems that provide certainty for developers and allow for adequate development to sustain affordability but, if we look at either Spain or the USA where there is no centralised planning system, what we see is the result of choices to use urban containment compared to choices to permit development at scale. The difference in affordability, of rents and house prices, between constrained Barcelona and liberal Malaga is very striking and we see the same pattern in the USA where Californian style urban growth controls result in much higher housing costs than in Tennessee, Florida or Texas despite those latter places having significantly higher rates of inward migration.

The case for densification is entirely and narrowly economic - claims of agglomeration effects and the viability of urban transport systems are presented as the benefits of dense development. Plus of course the 21st century’s favourite trope - low density development is car dependent and therefore a bad thing. This approach is not only myopic, people are not getting rid of their cars any time soon, but also presents the same short term economic preference as we see from the government’s childcare proposals. Creating places founded on family, children and community rather than work and hedonism gets rejected because planners want to believe in agglomeration effects and don’t want their precious tram system to lose quite as much money.

“There is an urgent need to do something about the housing crisis, but we shouldn’t do this at the expense of family life. Record low numbers of young children should be a wake-up call for those who argue for ever more crowded cities, for technocratic fixes like subsidised childcare, who want to sustain the sociological disaster of a world directed entirely towards economic productivity. A world that gave us depressed adults, stressed children and now, a generation of people who have no real stake in the society that demands their productivity.

What we need to do is build that new suburbia, to provide places that aren’t focused on productivity and the momentary pleasure that makes this grind bearable. We need places that work for children, who can be afforded off one middle-class salary, and which provide an environment that tells us work isn’t everything. We need to compromise again with the Taylorist world of the technocrats by saying that we don’t work to make money for the sake of money or, god forbid, to pay the taxes so we can get cheaper childcare and thereby earn more money to pay more taxes.

A new suburbia is about a family being able to sit in their own garden, surrounded by good comfortable things and looking at the home they own. And as the sun shines, that family knows that the efforts they made were worthwhile. Mum and Dad can look at the kids larking about in a paddling pool or bouncing on a trampoline and take pleasure in knowing that life’s not all about work.”

When I was a child, child care was provided by parents. The State provided none, and fathers would have been ashamed to admit they could not provide for their families. Mothers went to work, not to ‘have a career’, but to augment the husband’s wages so the family could have more ‘luxuries’ - like a washing machine for example. I an weary of people insisting the State should do more - as Margaret Thatcher pointed out, the State has no money, just taxpayers’ money. When the State is dishing out childcare, where will the money come from? Out of everybody’s pocket making every parent poorer and those children poorer too. And since the State won’t be able to raise enough revenue to cover its largesse, they will borrow. And who will pay back the debt? Those children currently receiving that childcare - unless we finally do destroy our economy by insisting the State pay everything for everybody so nobody needs to work, just sit hands outstretched waiting to be filled with cash. Time to kick the welfare State into touch so people have to start taking responsibility for themselves.