The Curse of Patrick Abercrombie

How the green belt, a well intended policy, means Londoners pay more rent and a higher mortgage. And how some of this might be fixed without scaring the horses

The idea of containing urban development so as to protect a sort of bucolic ideal is not new and neither is the restriction of development as a means of social control. Both Elizabeth I and Cromwell sought to constrain the growth of London, to control plague rather than prevent the naffness of suburbia. In the early 19th century J. C. Loudon, more remembered for inventing suburban garden design, called for a “green girdle” around London so as to preserve access to open countryside for the metropolis.

The creation of a London County, however, put rockets under the idea of containing the city’s expansion an avalanche of reports and proposals between 1890 and 1910 most notably from William Bull (1900), Lord Meath (1901), and George Peplar (1911) setting out how a green belt or parkway should be set around London so as to prevent its uncontrolled expansion. The ideas were adopted by the LCC and promoted by people like Raymond Unwin the designer of Letchworth Garden City. In 1935 the now Labour run LCC adopted a formal green belt policy and began to provide smaller local authorities beyond their boundaries with the funding to buy up land so as to protect it from development. The council sponsored the 1938 Green Belt (London & Home Counties) Act that formally set out the idea of a green belt in statute.

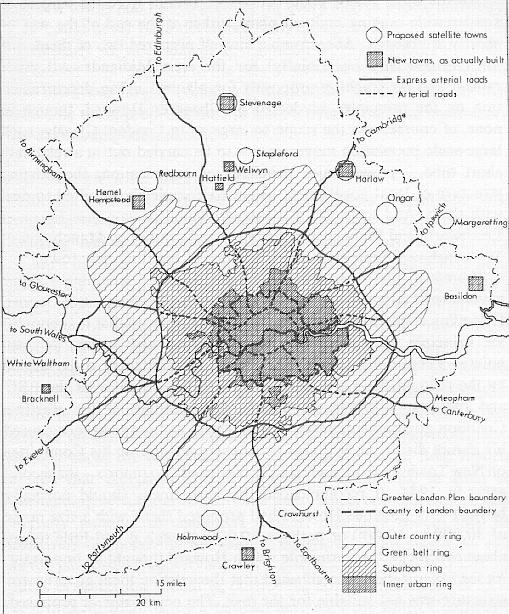

In 1944 Patrick Abercrombie, having already produced a plan for the city itself, produced a Greater London Plan. This plan set out the scope of the London green belt and spoke at length about the problems of urban sprawl and the terrible iniquities visited on London and the Home Counties by the housing boom of the 1930s (when private developers, unconstrained by the likes of Abercrombie, built over 300,000 homes a year shaping the suburbia where I grew up). The green belt is literally a consequence, at least in part, of the success of private housing development.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that Abercrombie was chairman of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (now the much-loved NIMBY charity CPRE) and sat also on the council of Ebeneezer Howard’s Town & Country Planning Association. It is fair to say that, Abercrombie, Howard and the new towns movement were much more interested in the country part of town and country planning.

The green belt is a well meant policy even if we disregard the slight tinge of snobbery that is associated with most urbanist and architectural writing about suburbs. But by the 1960s there was “intense competition for land on the urban fringes” as David Thomas put it in his 1963 review of the London green belt’s history. Even with the new town policy it was becoming clear that the impact of constrained land supply for anything other than agriculture or current use would create an affordability problem.

By the 1970s and despite a generally declining inner urban population across much of England, Sir Peter Hall could write that the planning system is inconsistent “with the objective of providing cheap owner occupied housing” and that it has imposed its greatest burdens on lower income households. The green belt - urban containment - had become a curse. People attached themselves to the brand and politicians indulged such people with cries of “save the green belt” and claims the “green belt is under threat”, while the lack of new homes worked like a warm bath of wealth creation for millions. The home my father bought for £17,000 and change in 1976 became worth £500,000 by 1997, today a home like this would be well over £1,000,000.

And the main reason for this obscene rise in house values is that we pretty much stopped building new houses in an around London. Worse, the expansion of London’s population from the mid-1990s exacerbated the lack of land for housing. Nearly a quarter of London’s land area is classified as green belt and for neighbouring councils like Sevenoaks and St Albans green belt makes up over 80% of the land area. It is true that there are brownfield sites within the areas of urban development and that we can build more densely but both of these options are constrained as well - by the way we protect urban environments (listed buildings, conservation areas, urban green space) and by additional costs of reusing previously developed sites.

A couple of years ago I wrote that we simply can’t meet housing need without reforming the green belt. For all its good intentions Abercrombie’s plan of 1944 has become a curse. And the victims of that curse aren’t the fortunate ones who bought property in the 1980s or even 1990s but the millions of Londoners with high skills, good jobs and good earnings but no decent home. The people who, in the 1960s comfortably afforded a three or four bed home in Sidcup, Hornchurch or Cheam.

“The reason London has a crisis of housing affordability is not because of developers, not because ‘brownfield’ land hasn’t been recycled, not because of insufficient density, not because of too cheap mortgages, not because of immigration, not because of the success of London. The reason London – and now Brighton, Bristol, Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Manchester – have unaffordable housing is because of urban containment, because of that ‘green belt’”

We could set about reforming that green belt, recognising that it serves some value but also that we need greater flexibility so as to meet current and future housing needs. We could:

Remove everywhere within 200m of a rail or tube station from the green belt. This wouldn’t remove other protections within the planning system (anything from wildlife habitats to floodplain) but it would, without compromising the purposes of the green belt, allow for a substantial addition to land supply for housing

Change the treatment of brownfield land within the green belt. Currently most brownfield sites in the green belt are treated in exactly the same manner as greenfield sites. Any impact on “openness” results in a refusal so nothing gets built. Brownfield’s definition also needs clarifying, and maybe re-naming, so as to show that it includes airstrips and golf courses as well as ruined barns or industrial sites

Allow self-build housing within the green belt and give greater flexibility over the redevelopment of redundant agricultural buildings and facilities. With the consolidation of agriculture, there are thousands of former farmyards, barns and other essentially brownfield sites that could be used more creatively for housing or small industry

Where the green belt “washes over” small villages and hamlets treat infill within these places as acceptable development and allow new build in gardens. These are urban spaces even if the idleness of planners has not taken them out from the green belt. I live in such a place where a former mill entirely within the green belt was converted and a dozen new build properties permitted. We need policies that encourage this sort of development.

None of these fully resolve the problem but they would all help in getting more development into the places where people want to live but constrained land supply made obscenely expensive. Ideally some sensible future government (if such a thing were ever possible) will conduct a full review of the London green belt - a new Abercrombie Plan as it were - but until that time comes the sort of limited changes to green belt policy above might just help. And may not scare the horses (literally and figuratively).

I was brought up on the edge of the green belt, and now I'm back living there with my parents because of the 'housing crisis.' You cannot imagine the opposition of people, largely 60+, to even the thought of a brick touching grass. Leaflets through the door, community meetings, consultations with solicitors etc. These people only seem to leave their houses to get involved in stopping the building of them. It's become a hobby. Quite possibly a religion.