The myth of working people

When politicians says ‘working people’ they use a convenient shorthand to describe people who aren’t blank, anonymous, distant others - the imagined rich

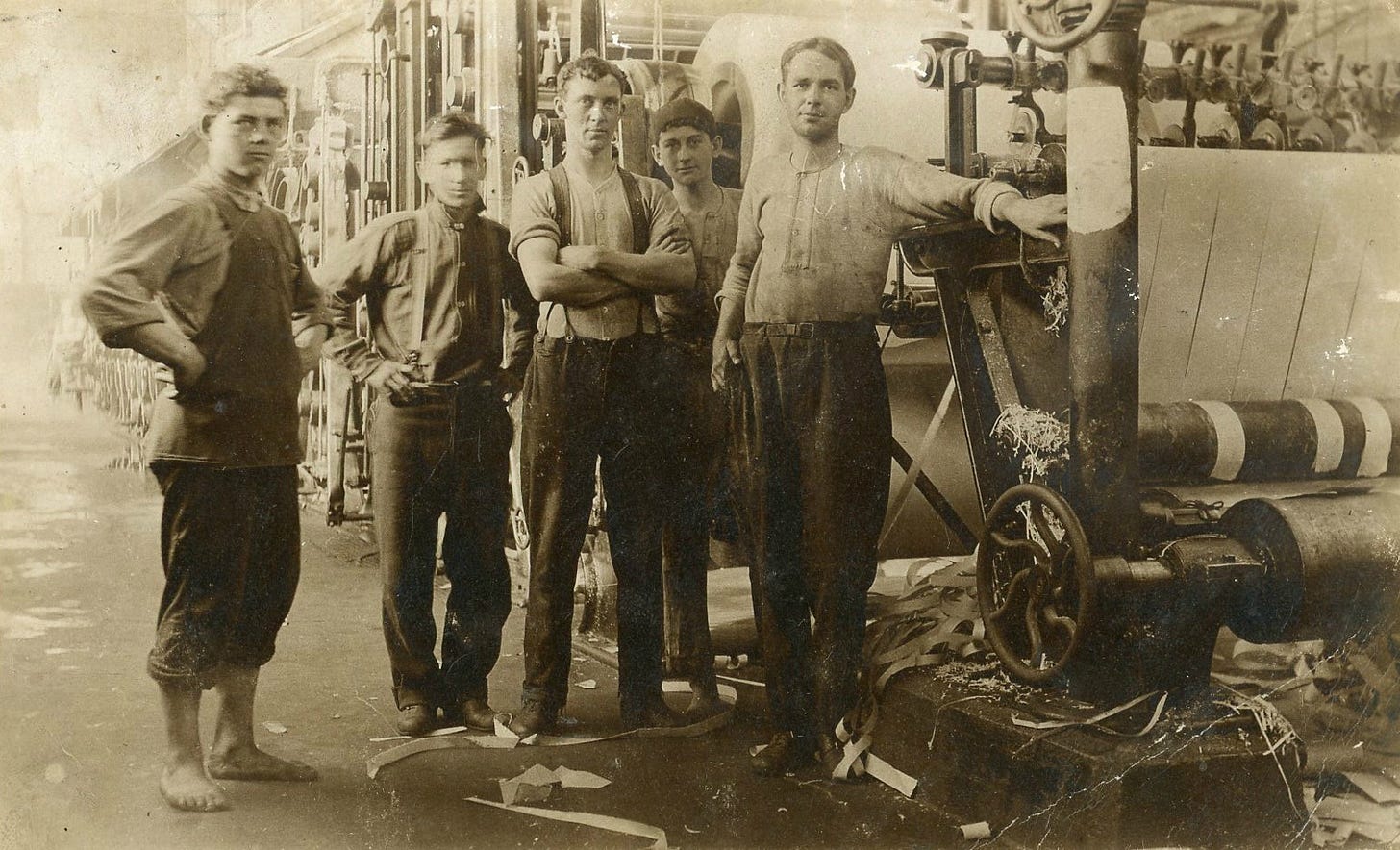

Ed Pickford, son of Durham miners, socialist and poet wrote ‘The Workers Song’ best known as performed by Scottish folk singer Dick Gaughan. I suspect that, when he wrote the song, Pickford was very clear in his mind what he meant by a worker. I’m no sort of socialist but the sentiment of Pickford’s song, “we've never owned one handful of earth” and “...yoked to the plough since time first began”, point to the worker being someone who owns nothing but the sweat of his brow and a cupboard of chattels.

Lawyers, council bureaucrats, businessmen and cabinet ministers, regardless of their back stories, are not workers. Such people may, as our current Chancellor of the Exchequer claims, ‘have the back’ of workers but even if they wave red flags and sing songs about strikes or revolution they aren’t workers. The problem is that the old workers versus bosses (and the agents of bosses, those lawyers and bureaucrats) idea was always mythic, an enchantment woven by singers and activists.

One of my favourite folk songs is Steeleye Span’s ‘Hard Times of Old England’ which tells us of a man bemoaning where the trade has all gone and asking what a poor man and his family is to do? The song, about a tradesman not an industrial worker, is from the time after the Napoleonic War when England was in recession. The man is clearly a worker - “Come all brother, tradesmen that travel along” - but more akin to todays ‘White Van Man’ than to the industrial workers Ed Pickford sang about. Our tradesman may have no work, may be worried where his family’s next meal is coming from, but he has no boss (or pension, or health insurance or sick pay). We are reminded that our characterisation of who is or isn’t a worker is a reflection of an industrialised (and now post-industrial) economy.

Interviewed today Bridget Phillpson, who often proclaims her working class origins, when asked what defined a ‘working person’ found herself explaining that she was a working person because she depended on her £160,000 salary as an MP and cabinet minister. The implication here is that the definition of a worker is someone on a wage - any wage - rather than the tradesman having a hard time in the 1820s. Indeed, when Phillipson is reminded that the average post-tax profit for England’s small businesses is £13,000, she can’t untangle the contradiction of the two girls running a village cafe being denied the title ‘working’ because their income derives from the profits of their cafe.

When millions of men worked in industry the idea of the worker was plain. We saw the difference and, as Disraeli advised, sought to improve their conditions. The Labour Party saw it as their mission, just the one not Keir Starmer’s multiple missions, to represent those industrial workers, to be the political arm of their struggle for rights and a better standard of living. We can argue about how it happened but the truth today is that workers do have better rights and a much higher standard of living. And one outcome of this is that workers are no longer as Ed Pickford describes, they do own a handful or earth, they aren’t yoked to the plough. Today’s workers have houses they own, savings and pension pots, and a scale of disposable income past generations would boggle at.

There once was a sense, although never as Karl Marx oversimplified, of distinction between those whose income came from labour and those whose income came from capital, rents and land. In the minds of today’s socialists this still pertains as they speak of ‘rebalancing’ the taxing of labour and capital as if our modern workforce (indeed any workforce since the end of feudalism) can be so conveniently divided. Today the largest part of people who do not work are the retired, living off pensions and savings, not the imagined rentier classes of socialist imagination.

We have a troubled relationship with the idea of work. This isn’t to suggest that people are lazy but rather that we mash together a collection of myths and misconceptions using terms like ‘working people’, ‘hard work’, ‘good jobs’, ‘business’, ‘stocks and shares’ and ‘unearned income’. It is plainly ridiculous to say that the owners of a typical small business don’t work and usually work damned hard. Yet the opposite is often the logic of our teenage marxist analysis of business and industry. I recall listening to my barber talking about what he called the ‘mistake’ of dividing his income by the number of hours he’d worked. The conversation ended with him saying ‘minimum wage, I wish!’

When a politician says ‘working people’ he or she is using a convenient shorthand to describe people who aren’t rich. This works well when it is merely rhetoric since the listener makes his or her decision to define themselves as a worker. Indeed that is the whole point of this rhetoric, the politician manufactures a distinction between everyone listening and a hypothetical ‘them’ - blank, anonymous, distant others: the rich. Speaking the other day with a friend about the budget, he observed that when he said ‘the rich’, he didn’t mean those rich (essentially middle class people) but those rich (basically Jeff Bezos). We want there to be a plain distinction between people who own things and people who go to work.

The problem is that there isn’t (nor has there ever been) such a clear distinction. Even when the nobles trooped into the King’s castle to put their taxes on a chequered table under the watchful eye of the King’s chancellor there was still a blurred edge between the realm’s different estates. Nor was there a time when (with apologies to PG Wodehouse) many people could swan around living high on the hog off income from unspecified ownerships and investments. The reason younger sons were shoved off to be priests and soldiers is because those jobs came with an income not merely to get them out of the way.

Today most of our businesses are owned by those who work in them and much of the rest of industry and commerce is vicariously owned through pensions, mutual funds and savings. And people don’t see their income from these investments (or their capital growth) as ‘unearned’ but rather as their prudent use of the money they have earned from working. Just as the landlord sees the home he rents out as his savings and the small business owner banks on selling his business to provide a pension income, the worker reckons that his savings and investments will provide for a good income in retirement, the funds to provide care and maybe a good inheritance for their children and grandchildren. Truth be told nearly all of us are rentiers these days. Maybe one of these days politicians will catch up.

Remember an article about "why it's hard to raise taxes on unearned income". The author's most interesting take? "The Petite Aristocrat Problem". Basically, most aristocrats weren't rich, but they didn't have to do physical labor for their often peasant-level (but often untaxeuntaxed) incomes. Substitute "retirees" for aristocrats he concluded, and that's why it was so hard to raise investment income taxes.

Excellent article Simon. I have just bought 'The Living Dead - The Shocking Truth about Office Life ' by David Bolchover. It was recommended by Andrew Orlowski at the Battle of Ideas and describes the extent of non-work that takes place in offices. I worked in a large corporation for many years and most middle management time was wasted keeping everyone 'in the loop' on email or in meetings or 'reporting' and 'planning'. 'Doing' was the process of simply being a manager. The growth industry, in its own right and within companies, are the consultations, measuring, auditing, performance indicating, setting targets on managing what already exists. Every small company that wants to work with a large organisation, private or public, has to be assessed and often certified in a range of factors that are irrelevant to do what they do - from 'environmental audits' that measure CO2 to demonstrating that your supply chain doesn't employ slaves. This is not work, it is in non-work. Perhaps this non-work should be taxed out of existence?