There is no economic benefit to shopping local

Local shops succeed because they are themselves a high-status good and the fact of cherished independence provides most of that advantage

When I started my masters degree dissertation (it is titled ‘The Economic and Social Impact of Street Markets’) I did so assuming that the local multiplier effect was an uncontroversial idea and largely true. My supervisor suggested that, as part of the work, I should look at the theory and wider research around the local multiplier. After all, if I’m going to do a real world test of a model for the local multiplier (in my case a system called LM3 designed by the New Economics Foundation) then looking at the theory matters.

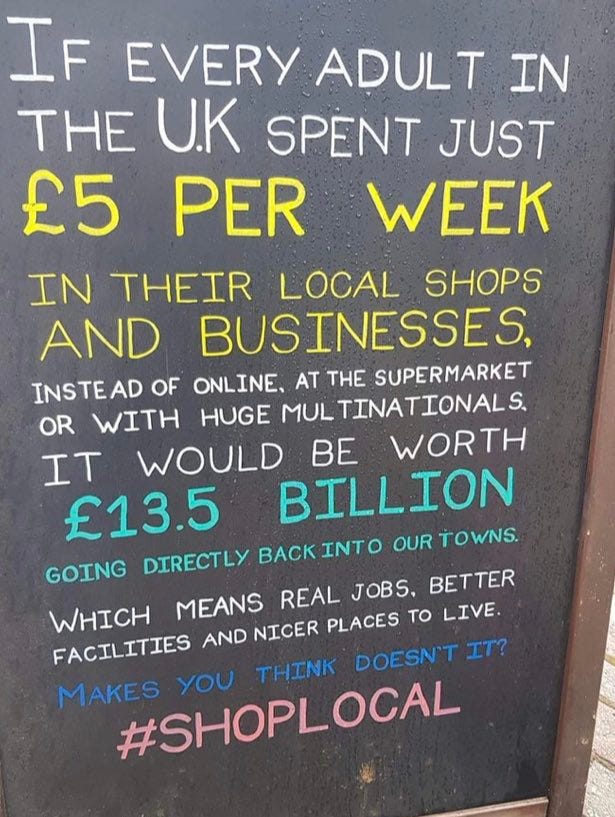

All this brings me to the picture above which describes the popular understanding of the local multiplier - by spending with little local businesses, more money is retained in the local economy meaning the local economy does better. The problem with this idea is that its central claim isn’t true:

“...here we have the problem - that reference to 'local supply chains' will be familiar to anyone reading the output of CLES, NEF and NWI. It refers to the view that local supply chains keep more money within the community than supply chains based on the national economy. The idea of the local or regional multiplier is central to this assertion - NEF make a good living from plugging their LM3 model to all and sundry (despite it having no real theoretical basis or any robust empirical support). The problem is that the local multiplier is something of a myth - the impact of excluding national supply chains is, in effect, the same as any act of protectionism. So any gain from having the money circulate within the community for longer is lost in that community having to pay higher prices.”

To this price effect we can add the problem with defining what we mean by a local economy given that models of local economies such as LM3 seldom take account of the input source (e.g. where the money being spent is earned) plus the eternal problem of economic geography, where is the boundary of your local economy? The poster in the picture contains some simple maths in making its claim but, in doing so, ignores some other maths that we need to consider. Yes all those five pounds add up but we should also ask where the five quid we spend goes and whether it, in reality, more money goes into the local economy than would be the case if the purchaser went to the supermarket, a shopping mall or bought online.

The biggest part of that £5 you spend in the local shop (and remember that you have already opted, in most circumstances, to reject a choice that would be cheaper creating an opportunity cost) will go on the cost of goods for the retailer. Obviously this cost will vary depending on the type of shop but we can expect that a good proportion of the goods bought for resale will be from outside the particular local economy - perhaps half of the five quid has already left the local economy before we’ve even spent it.

The shop also has other costs that involve money leaving the local economy - taxes, rents, energy costs, insurance, security - meaning that the amount ‘recirculated’ gets smaller and smaller. This is one reason why local currencies such as the Bristol Pound fail - most of the costs for the retailer fall outside the local economy. You can’t pay your taxes, rents or energy bills with non-legal tender issued by a credit union. And to make matters worse, the part of the five pounds we spend that is retained by the person owning the shop (or paid in wages to people that person employs) is also largely spent outside the local economy.

Think about your wages for a second. The biggest part of your income goes on taxes, rent or mortgage, and energy costs. None of these payments goes into the local economy, indeed the discretionary part of your spending is only done after essentials are met. Local shops, either because of their inherent price disadvantage or else because they sell non-essential goods or services, do not take up anything more than a minority of our expenditure. And this is true even when our income comes from running a local shop. Perhaps 10% of that five quid we spent contributes to “real jobs, better facilities and nicer places to live”. And it is moot whether this is really much different from spending the five quid in the supermarket.

Please don’t take all this as an argument against local shops but the success of local high streets and independent retail isn’t determined by a choice to spend money without consideration of choice or quality. There is a reason why places with lots of well-heeled residents and visitors tend to have more and better independent shops - levels of discretionary spending are higher because people have more disposable income. It is a whole lot easier to make your high street great in Ilkley or Hebden Bridge than it is to do so in Manningham or Keighley. As I observed recently writing about Bradford city centre:

“...problem is, I would say now and then, that we really want to be a ‘Consumer City’ not a ‘Producer City’. It isn’t that we don’t need jobs, industry and commerce but rather that the places we talk about whenever city regeneration is mentioned are all focused on consumption - leisure and pleasure - rather than the dullness of work, of production.”

So, if you want a better high street, the answer isn’t to try and corral all the money within that community (because that is literally impossible) but to work out how people shopping there have higher levels of disposable income. Economic growth across the wider economy is clearly essential for this to work but there are other actions available to governments - reducing taxes, changing regulatory constraints on business such as planning rules, supporting the infrastructure needed for cheap energy, and allowing more development so as to reduce rents and mortgages.

Local shops succeed because they are themselves a high-status good. It may indeed be true that the meat, fish, greens or clothes sold in the local shop are higher quality than those sold in the supermarket or the international retail chain but this is not, in and of itself, the reason for the local shop working. That shop’s success or failure depends largely on the ability to position itself as superior and the fact of its cherished independence provides most of that positioning benefit. But the benefit only comes so long as the local shop is in a market with sufficient disposable income for there to be buyers of the shop’s high status offering.

Local shops and great high streets are really important (as are street markets and market halls) but we need to reject what I call local protectionism because all that does is damage actual local economies by making things more expensive by reducing choice. The lost opportunities inherent in local exclusivity more than outweigh any benefits from local protectionism, even if you call it an ‘inclusive growth strategy’. And this is assuming that there is any effect from a local multiplier, something which is at best marginal and, in most cases, non-existent.

Broadly agree, but a couple of thoughts:

1. It assumes that most goods are sourced from similar sources to their supermarket/online equivalents. Is there an impact if you say that there might be, for example, consumables made from produce grown locally?

2. This seems to measure benefit to the local area in economic value alone. Obviously hard to measure, but could you consider that the benefit of the extra spend is supporting a nice local high street: you are willing to buy posh farmers market jam so that in the future you still have the opportunity to buy posh farmers market jam?

Taken to its logical conclusion, if everyone just donated £5 a week to local shops it would have a better effect because there would be no costs to the retailer. It’s a pity more people don’t read Adam Smith: “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; the interests of the producer are considered only as much as they benefit the consumer”. I don’t shop to keep anyone in business, but to serve my interests be they convenience, variety, quality or economy, and certainly not the local community. Born in 1952 in a small village nearly all shopping was local, and most food production was local, seasonal and mostly organic - the fantasyland of the eco-freaks. Local shopping worked because all the shops were within a few minutes walk, people did not have fridges/freezers or big pantries, and so people shopped for small amounts daily - no supermarkets then. Also some retailers, butcher, green grocer, milkman came round in vans, some with horse drawn carts too like coal merchant, ice cream vendor, fish monger. Local, seasonal, organic produce sound great, but vegetable were often riddled with bugs, in short supply therefore more expensive as the season progressed, and second harvests were usually of poorer quality, and of course it was all weather dependent. Fruit and veg not native or not grown locally were just not available. Seasonal meant the same things for weeks on end. In short: local shopping meant you bought what the retailer had and not necessarily what you wanted, and at a take it or leave it price. Things have changed so much which makes local shopping except for boutique, specialist or convenience stores redundant. The solution to abandoned high streets, is allow the property to be developed for habitation.