Why needing to build lots more new homes means we have to scrap our current planning system

It wouldn’t be a free-for-all but a market where the arbitrary determination of land use to suit political preferences no longer stops people having an affordable home of their choice

Although the tide of debate around housing in the UK has shifted towards a more pro-housing position, there remains a worrying tendency for people commenting on housing to ignore basic economic principles because doing so suits their position. Now I appreciate that the CPRE is the NIMBYest of NIMBY organisations and that its London branch is even NIMBY-er but this article from CPRE London’s ‘Head of Green Space Campaigns’, Alice Roberts is a perfect summation of the problem:

“Dig a little deeper and you get the ‘supply and demand’ argument: ‘increasing housing supply will bring prices down’. But this logic doesn’t work if demand stays high. And in any event, housing markets are much more complex. Supply doesn’t tackle tenure or distribution issues. Housing markets are usually highly regulated for this reason.”

There is a great deal more egregious claims in the article (about right-to-buy, household numbers, the definition of green belt, and planning permissions) but it is probably worth a few words explaining why the basic laws of supply and demand really do apply to housing markets despite the best efforts of governments, housing ‘experts’ and campaigners to tell us otherwise. I appreciate that it is a tad worrying that this needs explaining but take a look at this from Ms Roberts:

“Should we introduce rent caps? Should we stop fuelling house prices by subsidising house-buying with ‘Help to Buy’ schemes? Should councils have the means to build new social housing? Should we actually ‘level up’ between the north and south of the country to take the heat out of house prices in the south? Should we take action to bring empty homes into use? Should we reform the current land value capture mechanisms (S106 and CIL)?”

This is an attempt to cope with the problem you get when you refuse to recognise that, if you want more affordable housing then the best way to get it is to build more houses. Plenty has been written about the disaster of rent caps, we shouldn’t subsidise housing purchase, councils should have the means to build housing should they wish, no we should not try to move everyone to places where their job isn’t, and increasing taxes on development results in less development. But really we need to build more houses.

When people, even enthusiasts for more housing, talk about the dynamics of house prices, they will tend to focus on the total quantum of houses in the country, region or local housing market. Yet, as we all know, most of those houses are not available for people to buy because their owner is happy living there and has no intention of moving right now. What we need, when we talk about how house prices (and, for that matter, rents) change, is to talk about inventory - how many homes are available for people to buy or rent at any given time.

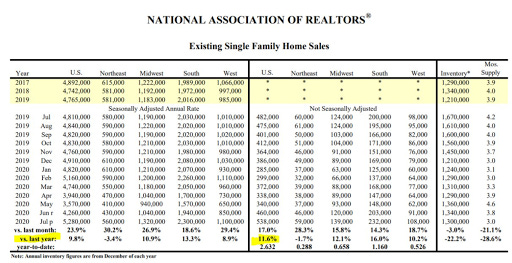

This table is from the USA (where data on inventory levels is more easily available) and, as I wrote at the time:

“US house prices are showing a 5.4% rise year on year and this table gives us the reason. Sales are 11.6% higher, perhaps something of a response to the hiatus of the pandemic, and this reflects a surge of buyers entering the market. At the same time the NAR is reporting an inventory - the numbers of properties on their books - that has dropped 20% compared to the previous year. So fewer homes for sale and more buyers means, boom, a rise in house prices.”

If you want to stabilise house prices then the aim has to be that the number of buyers in the market at any given point equals the number of sellers. And the way to do this is to allow the market to function without the constraints that come from our planning system and especially from the green belt policy. This doesn’t preclude regulations about building standards or protections for important heritage and environment but it takes us away from an essentially arbitrary and judgemental focus on ‘sprawl’ and preventing urban growth. Indeed, as the chair of Natural England has observed, blanket policies like green belt are not great at protecting the environment:

“The green belt should not be sacrosanct," he says. England could end up with less green belt than it has currently, but “better quality greenbelt – that might have more houses in it. If you look at many green belts around England, quite a lot of them are pretty bereft of wildlife. They’re not very accessible. Some of them are not producing much food either.”

Instead of a blanket defence of green belt land, government and local communities should take “a more joined-up view” that could see some new building but better conservation, and more green space where people need it.”

There is no way in which you can, even with sophisticated housing need models, plan for a housing market where levels of inventory exceed current demand. And part of the problem we have rests with the suppression of household formation implicit in a shortage of housing. This situation results in the repeated claim that we aren’t short of houses - as Alice Roberts writes in her article:

“and leaving aside the fact we have 1.5 million more dwellings than households: ONS/census data”

A moment's consideration will tell you that the number of available houses determines the maximum number of households - you can’t have, given how the ONS/Census define a household, more households than you have homes. What we do have, however, is lots of what are called ‘hidden households’ that would form if there were homes available for people to move into that they could afford. The ONS has surveyed this problem and identified that there were 1.6m ‘concealed’ households (an adult living in a household who would prefer to rent or buy) and 500,000 ‘sofa surfers’ (households reporting someone living with them who would otherwise be homeless). That is over two million households that are not ‘counted’ as households before we consider other dynamics such as shared houses, bedsits, delayed marriage and motherhood, overcrowding, and divorce. The existence of advice pages and support for divorced couples sharing the same home suggests that housing remains not only a barrier to divorce itself but also results in unsatisfactory living arrangements.

Inventory matters and the make up of that inventory matters too. In UK housing markets most of the inventory (around 80%) is second-hand, meaning that the dynamics of the market are very different to one where a higher proportion of that inventory is new build (think about housing chains and how people make decisions to move or sell). There are arguments that you could, for example, increase inventory by incentivising people to downsize - to get a little more velocity in the market - but this assumes that people really are looking to move from their three- or four-bedroom home to a smaller flat or house. Even with our sclerotic housing and planning system, you would expect to see more market for downsizing but the fact there isn’t simply reflects that 80% of this market don’t want to downsize.

The only way to stabilise the housing market (by which I mean having house prices and rents rise at or below the rise in incomes) is to have new build housing make up more of the total inventory. And because we do not really know the extent to which demand is suppressed by the planning system, we can’t plan for the numbers needed. The system of ‘Objective Assessment of Housing Need’ (OAN) used in the local plan process, attempts to accommodate this unknown by adjusting population growth estimates using guesses about economic (usually ‘Gross Value Added’) growth. There’s not a lot of evidence that these estimates are helpful, let alone accurate, suggesting that the ‘plan and target’ approach developed under Blair’s government and still central to housing policy is really part of the problem, not any kind of solution.

We really don’t know, and have no obvious way of estimating, the level of housing demand or the distribution of that demand. Indeed, this reality is at the heart of why planning systems (and especially the sort of planning system we have in the UK) contribute so much to housing crises. If we guess the number of homes we need wrong (and we will), then guess the amount and type of homes wrong (and we will), then allocate land to meet these guesses, the result will be the wrong location and distribution of land for development. This is then made worse if we, in effect, ban new homes on over a third of the land available and on 80-90% of the land available in the places with the greatest housing pressure.

The housing crisis in England is almost entirely down to there not being enough houses but, just as importantly, if we want to fix it, we need to see the numbers of new homes built exceed the overall demand for housing. If we don’t do this, even if we do increase the numbers built, then house prices and rents will continue to rise. Labour’s target (and the current government’s ‘ambition’) of 300,000 new homes per year is not enough to deal with the known latent demand, those 2 million households that would form if there were the homes available, let alone demand pressures from unknown hidden households, immigration and other new household formation. Moreover, we cannot expect that new housing can only be delivered via a ‘local plan’ and the existing housing development industry. In Austria nearly two-thirds of new homes are individually built, almost always by the people who go on to live in them, in the UK this self-build represents less than 10% of new homes. Instead we rely on a half dozen companies to build 80% of new homes, a situation entirely consequential on our planning system.

In an ideal world, we would repeal the 1947 Town & Country Planning Act (and subsequent planning acts) and replace it with rules on building safety and protections for heritage or environment. It wouldn’t be a free-for-all but would be a market where the arbitrary determination of land use to suit political preferences no longer constrains the ability of people to have an affordable home of their choice. We probably won’t get this situation but the UK really should make substantial changes to how it determines what gets built and where, starting with the abolition - or substantive reform - of the ‘green belt’.

I have never seen a sensible argument from the likes of Alice as to why the most fundamental law of economics should not apply to housing. They might like to look at almost any other country in the world, but Europe would do, to see that supply and demand is working perfectly adequately, there is not a massive shortage of housing and it doesn’t cost ludicrous multiples of the average salary to purchase.

The likes of Alice won’t look because they don’t want to see. They have an ideological commitment to keeping the country broadly as it is. If they had had the same attitude 100 years ago many of them would have to admit that the house they live in now, and they consider to be perfectly in order to exist, would never have been built.

I agree totally with your recommendations. Get the politicians out of the way and the market will address the demand. Because that’s what markets do.

Or get rid of the height restrictions. A glance at the number of plastic lawns, or the number of paved frontages reveals an unpent demand for housing without a garden, so grant the permits for them to have a flat. For Councils that have declared climate emergencies, repeal the right to light, and allow up to 12 stories on the same foot print. Heck, the Council said we need to consume fewer resources per person and per living space, so give it to them good and hard. And if any Councils still object then grant permits to go Tiu Keng Leng. It's an emergency.