A folk revival? Maybe let's just sing some songs?

What matters isn’t a folk revival but that we have more people making music, singing songs and dancing. So there's always someone to get out an instrument and accompany the rest of us as we sing.

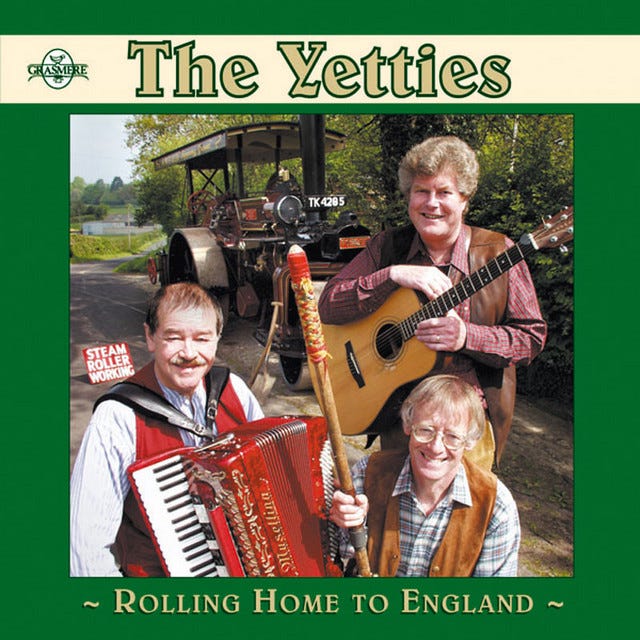

One of the first concerts I went to as a teenager was to see a folk band called The Yetties. They are probably long forgotten these days and, like many of the popular 1960s and 1970s folk groups, best remembered for comedy songs like ‘Costa del Dorset’ than for singing old songs. The Yetties were part of an English folk revival that is perhaps best remembered for giving us Jasper Carrot, The Spinners, Mike Harding and The Wurzels singing about combined harvesters. Plus, in Wales, Max Boyce singing about rugby players and saucepans.

The Yetties played and sang songs. There wasn’t any political message, no trendy rewriting of the words to make them more contemporary. When they sang Robert Hawker and Louisa Clare’s ‘Song of the Western Men’, they weren’t making a point about Cornish nationalism (not least because the band were from Yetminster in Dorset - hence the name) but just belting out a great song with a cracking chorus (doubtless twenty thousand Cornishmen would agree). For over 40 years The Yetties toured, performed and recorded - hundreds of Morris dance tunes, loads of traditional West Country songs (including dozens first saved by that excellent fiddle player Thomas Hardy) and a bunch of comedic ditties about the glories of Dorset.

I’m writing this because folklorist and fellow faerie enthusiast, Francis Young suggested, in a Spectator article, that we need a folk revival:

“...we might regret the absence of a great revival of folk culture in 20th-century England, as the redefinition of national identity suddenly came to prominence with the disintegration of Britain’s empire – and, indeed, the desire to recover some sort of folk understanding of Englishness might explain the folk-obsessed 1970s.”

Like Dr Young I feel the need for what we usually call ‘culture’ to have some connection with our roots, the land we shaped and shared, echoing the trials of past generations and the challenges of today. Folk duo, Show of Hands, sing a song called ‘Roots’ where the bemoan the way in which the English - their people - have lost their musical roots:

“After the speeches, when the cake's been cut

The disco's over and the bar is shut

At christening, birthday, wedding or wake

What can we sing 'til the morning breaks

When the Indians, Asians, Afro-Celts

It's in their blood, below their belt

They're playing and dancing all night long

So what have they got right that we've got wrong?”

Steve Knighley who wrote that song tells that it was inspired by then culture minister Kim Howells remarking in a House of Commons debate about licensing for music that three Somerset folk singers in a pub was his idea of hell (the context here is that you needed an entertainment licence to have three singers but not two).

There is an old definition of culture that I’ve always liked: culture is those things you don’t learn at school that are important. This strips away the snobbery that infests the sort of culture presented to us in the media and gets to the heart of the matter - songs, stories, jokes, legends, manners and rituals make up the cement of society and losing connection with these things or pretending them to be unimportant or even dangerous is a terrible infliction from the ‘cultural elite. Returning to The Yetties, their website tells the story of how they started:

“Pete Shutler, Mac McCulloch, Bonny Sartin and Bob Common (The Yetties) first met in the Yetminster Scout Group in the mid 1950’s. Singing round the camp fire and performing little sketches which developed into shows in the Church Hall to raise money for camping trips etc.. Then the Yetminster W.I. started folk dance classes in the hall every other Tuesday night and the girls of the village went along to join in. None of us boys actually lived in Yetminster at the time but the attraction of a bunch of lovely young ladies to dance with was too much so the village became our social centre. This developed into forming a young folk dance display team which performed their favourite Dorset dances at local fetes and festivals. The village down the road is Ryme Intrinseca so we were The Yetminster & Ryme Intrinseca Junior Folk Dance Display Team. This proved to be a bit of a mouthful for the M.C. when we went to the village of Offley, up near Hitchin in Hertfordshire, for their folk festival. He shortened it to The Yetties and the name stuck for the next 50 years.”

Most of the songs I know came from my Dad who, like The Yetties, learned them sitting round a similar camp fire with a similar scout troop. On occasion sat round the dining room table our whole family would belt out ‘The Lincolnshire Poacher’. ‘Tavern in the Town’, ‘Richmond Hill’, ‘John Peel’ and a bunch of other once standard English folk songs (plus because why not, a load of slightly tweaked English folk songs from the Pete Seeger collection).

The question Francis Young asks is important - where is today’s camp fire and what are teenage boys singing round it? Although there are plenty of scout troops and lots of village halls, I’ve a feeling that not a lot of community singing takes place around camp fires (assuming health and safety still allows these things). And if there is singing it won’t be old English folk songs but 20th century pop music - as Show of Hands sang:”... 'Duelling Banjos', 'American Pie', It's enough to make you cry, 'Rule Britannia', or 'Swing low...' Are they the only songs we English know?”

Folk music has, in England at least, two problems. Most people see it as a bit naff and nerdy even while they quietly enjoyed Simon and Garfunkel singing ‘Scarborough Fair’. And secondly folk music has too much of what I call ‘Billy Bragg Syndrome’, a desperate urge to be politically relevant, radical and edgy, to escape from that Ralph Vaughan Williams, Thomas Hardy and Cecil Sharp conservatism (literal conservatism - the saving and conserving of traditional song and dance). In part this latter problem merely reflects the former problem by suggesting that your nerdy love of old tunes is made relevant by talking about Gerald Winstanley and The Diggers or getting some African drummers to ‘reimagine’ ‘On Ilkley Moor’.

Although there is, as Francis Young notes, some revival in Morris dancing (usually accompanied by slightly sneering comments that would never be directed at Kala Sangam’s traditional Indian dance) and folk music maintains a loyal following, it is hard to see another revival - unless, that is, Taylor Swift decides her next album will be traditional English songs, in which case all bets are off! Perhaps Young’s observation “...(i)f folk music remains frozen it is, by definition, no longer of the folk – no longer the music spontaneously made by ordinary people” gets us closer to the truth. What Vaughan Williams and others did travelling the land collecting songs was an act of historical importance but, once the song was written down - frozen - it stopped being ‘folk’ music and became just a song? Maybe the problem here was also that unlike country music’s Carter Family, Vaughan Williams and other English collectors weren’t writing down the songs so they could perform them on the radio to an audience of millions. Instead they were tidied away neatly in a catalogue and used as a source for what we’d call ‘classical’ music. I’ve often joked that Vaughan Williams didn’t write an original tune in his life (which is probably unfair but does reflect the extent to which he plundered folk song for his work).

I’ve believed for a long while that we need to hold hard onto traditions - even traditions like the Oxenhope Straw Race that was dreamt up by some blokes in a pub about 50 years ago. And music is one of those traditions. It probably isn’t the case so much today but there was a time when you could recruit a brass band from any terraced street in Queensbury. Every family in the town had at least one member who could give you a tune on a cornet, trumpet or trombone. There was the great Black Dyke Mills Band of course but also the Queensbury Band and at least two bands from Queensbury School. Across the north of England choirs and bands, often formed (like cricket clubs and football teams) in mills or churches, created a tradition of music now largely lost. What little we retain deserves more attention than it receives and certainly as much attention as we give to the dance, music and traditions of the immigrant populations that add to and enhance our culture.

In the end Louis Armstong was probably right when he said "Man, all music is folk music. You ain't never heard no horse sing a song, have you?". What matters isn’t a folk revival but that we have more people making music, singing songs and dancing so when the TV stops and you can’t get Spotify on your phone, some of the company can get out an instrument and accompany the rest as they sing and dance. There are lots of things that could help this happen - more music in schools and more support for music’s grassroots from the likes of the BBC - but perhaps we should start by just singing some songs? Here’s The Yetties doing just that.

"What matters isn’t a folk revival but that we have more people making music, singing songs and dancing so when the TV stops and you can’t get Spotify on your phone, some of the company can get out an instrument and accompany the rest as they sing and dance."

We have so many levels of redundancy in everything that this is unlikely to be a problem. Those who want to sing can still join choirs and groups, of course, but a family no longer has to get their child piano lessons to sing around it.

But it's also the case that more children than ever are learning a musical instrument. All this modern tech has made guitars and keyboards cheap. The internet makes teaching cheaper.

And I'm with Louis. I think there are some beautiful folk songs from the past, but I hear folk songs about people having to cross the water from Plymouth, and that's not really a modern problem. Much of our modern folk is in pop. People will join in with Angels by Robbie Williams, or some of Coldplays songs. I think the Beatles are very much our more modern folk music sometimes. I think Dry Your Eyes by The Streets is quite folky.

Ultimately, things will go where people want them to. Government subsidy can't make up for what people want.

Made me misty eyed for communal singing on the bus as we went on the Sunday school picnic.

Ten green bottles etc. And being Scottish, and British I’m sure there were some English songs in there too. One of the first songs I learned on the guitar was ‘The Streets of London’ by Ralph McTell and one of the first live bands I saw was The Strawbs. Of course, in the 70’s we didn’t have the SNP polluting our culture. Great post and the earlier one on council funding.