How you read a letter and why this matters in today's online world. Trust me.

In this world, almost everything you see is fake and manipulative because without doing that you can’t get the attention needed to make the game work. Not being fake should be a winning strategy

“People hate advertising until they lose their cat.” (David Droga)

To appreciate how misinformation works, you should consider how people read a letter. We all assume that the reader starts at the top and reads the letter until that reader gets to the end. After all that’s how you wrote the letter. The problem is that people, including you, don’t read a letter that way.

You reading the letter begins with the envelope. You look at the envelope, check who it is addressed to, turn it over to see its return address and, if there are any, take in any colours, images and words. You’ll be much more engaged and interested if the letter is handwritten, if the envelope teases you about its content and if there’s a message urging you to ‘see inside’.

So you take out the letter and read it. Sort of. First you check the address, admire the colours in the header, and read the headline (if there is one) below the bit saying ‘Dear Your Name’. But then you’re going to look at the end of the letter to see who wrote it to you and, because that’s where you are, you’ll read the postscript, especially if it says ‘you…’ at the start. If you’re still curious at this point then it’s back to the beginning where you’ll read through the letter in the correct order, sort of. What you’ll actually do is skim over the boring bits and look at the underlined sentences, the sections in bold or red (or red and bold), and in particular the the bit in that text saying “...and you <your name> may have already won £1,000,000 in our free number draw…”.

The way you consume written texts helps explain how misinformation works (there’s a whole science about how people read a catalogue page) because it reminds us that getting our attention is the first task of any communication. And the thing that is most likely to grab our attention is our name. A few days ago I was in a queue for a cafe when from behind me I heard someone call out ‘Simon’. I turned immediately because that’s my name. As it happens it was also the name of the person ahead of me in the queue. And my attention went immediately. To keep that attention you need to make an offer or appeal such as that chance to win £1,000,000 in a draw (and, you’ve guessed it, if you say ‘you may already have won’ then you get more response than simply saying ‘enter our free draw’).

All of these triggers, attention-grabbers and tricks of the copywriting trade are not simply old wives tales either. Readers Digest, Sears, Grattan, Damart and a thousand other businesses tested all of them again and again. We know that long copy pulls better than short copy, that a message on the envelope lifts response, and above all that personalisation, however crude, always works. In a world of social media, algorithmic targeting and sophisticated data analysis these old direct mail truths haven’t gone away which is why the system tells you that you “...were interested in <product/ issue/ service> so might be interested in this <product/ issue/ service>”. And it’s why the old mail order trick of saying “you can see more” is used rather than “continued” (plus breaking halfway through a sentence to make you turn the page - the ‘cliffhanger’).

Knowing about these techniques doesn’t, even if you have years of mail order experience or a PhD in trigger words, make you less affected by their use. These methods work as well selling subscriptions to sophisticated academic journals as they do for collectible thimbles or knitting part-works. We are like a coiled emotional spring set into action by the right triggers. There are universal ones such as ‘free’, ‘savings’, ‘offer ends soon’, and ‘you have been selected’ but there’s one that really matters in disseminating misinformation; the ‘bestseller effect’. If I tell you that the jacket in the top right of the catalogue page (incidentally that’s where you’ll look first) is a ‘bestseller’, you are more likely to buy that jacket. And if my online message says “everybody is talking about <product/ issue/ service>” you’re more likely to respond. To boost this even more, let’s add something for you to respond to: a comments section, a like button, ‘share this now’, a poll, a petition. After all, another one of the direct mail rules is to ask the reader to respond repeatedly and to make that response as easy as possible. Advertising has no point if you don’t ask the reader or viewer to, ideally explicitly but sometimes implicitly, do something.

“If you're trying to persuade people to do something or buy something, it seems to me you should use their language, the language they use every day, the language in which they think." (David Ogilvie)

Advertising is not misinformation but if you want to direct people down a rabbit hole of lies, deception and bad ideas then the methods crafted by advertisers over the years provide a guidebook to getting your message across. There’s a category of online content where people self-identifying as journalists create content (you’ll see it called ‘auditing’) by manufacturing confrontation. Sometimes this is simply a function of latching onto protestors or counter-protestors and capturing video content that can be edited to fit a given agenda. But it is also done in remarkably innocent circumstances by targeting security guards, junior police officers or receptionists. Often, quite mild interactions are pushed using assertive language designed to appeal to the established opinions of the target audience. All of this is exaggerated but not truly misinformation (whatever the BBC may say). It does, however, help valorise other explicitly misinforming practices including staged and set up interactions, carefully scripted rants from car front seats, unevidenced engagement or confrontation and, as we’ve seen extensively from the pro-Palestine lobby, outright fakes.

Until the web revolution, we lived mostly in a non-direct marketing world for the simple reason that direct marketing was expensive and the more direct (think face-to-face sales) the more expensive. What the web did was to make direct marketing incredibly cheap resulting in an environment filled with people willing to take tiny response rates because the ads are so cheap. Until this happened we’d been largely guarded from direct marketing’s power and the techniques, some of which I’ve described here, while applicable, didn’t dominate communications, journalism and writing. Now, in a media world dominated by instant engagement and reaction, the people using these attention triggers best aren’t the mainstream of media and marketing but the inconsistent world of ‘citizen journalism’, ‘podcast’, TikTok and video-gramming. And in this world, almost everything you see is, to some extent, fake and manipulative because without doing that you can’t get the attention needed to make the game work. Worse, the mainstream of media and politics fights back by seeking to close down this new world or to try and expose it (see the BBC’s risible ‘Verify’ service) by counting tweets or making allegations, little more than conspiracy theory, about sinister news manipulation by (usually) ‘far right’ groups or individuals.

When I stopped being Account Planning Director for one of the UK’s biggest direct marketing agencies, we were still living in that old analog world, there were no smartphones, no social media and no instant ‘independent’ video coverage of everything. But the techniques now used online were the techniques we used everyday. That’s why I know how you’ll read a letter, where you’ll look first on a catalogue page, and what words, positioning and design will increase - substantially - the chances of you responding.

The problem is that bad faith actors in politics and business learned the tricks more quickly than a media and mainstream political world soaked in brand marketing, presenter talent and news management. One reason for outsiders like Jeremy Corbyn, Nigel Farage (plus the daddy of them all, Donald Trump) succeeding is that these people allowed those around them to use the ideas of direct marketing they saw on the web and craft them into a campaigning tool. All helped, of course, by proximity (accidental or deliberate, it doesn’t matter) to the people creating that, often bad faith, online ‘journalism’ and related content.

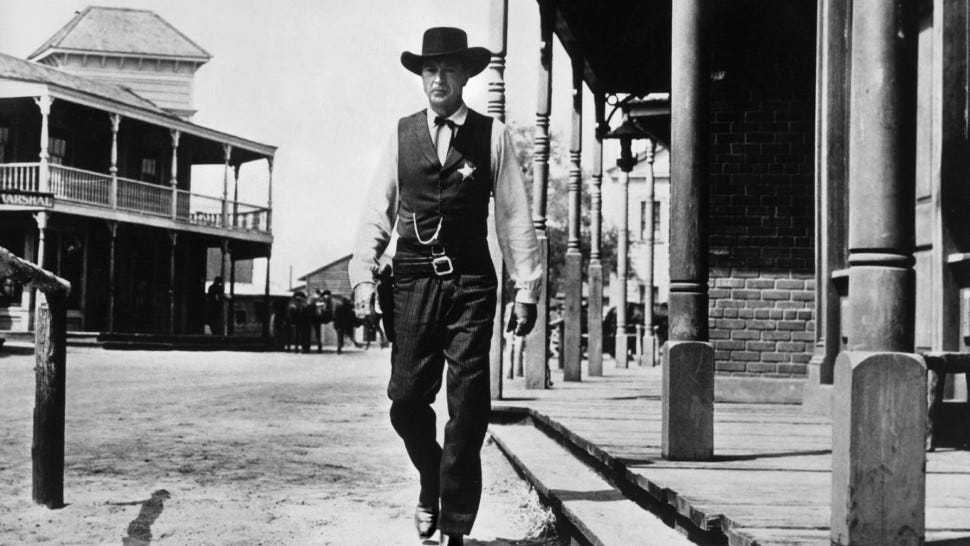

I’ve purposely written this all without links so you’ll have to trust me. I hope that my brand grants that possibility but recognise that it might not be. We are told (mistakenly I think) that we live in a low trust society which points towards being trusted as a central aim for anyone to succeed. If you’re out in the badlands you want to be Matt Dillon or Will Kane, not because of the badge but because of the man beneath. Trust me, I’m in advertising!

Rory Sutherland regards himself as lucky to have started in direct marketing and thinks the fundamental lessons it teaches are vastly important and transferrable.

Claude C Hopkins explains a lot about today’s world